WELFARE ECONOMICS

Socio-economic Status of Muslims in Western UP

Azim A. Khan, Professor & Academic Director, India: Health and Human Rights SIT Study Abroad, New Delhi 5/30/2011 11:30:49 PM

Among the issues that have been subject to extended public debates and discussions in recent years has been the issue of ongoing marginalization and under-development of the Muslim communities in India. Though much has been written about various marginalized populations and the means by which empowerment has been pursued, little empirically-grounded research exists on the social, economical and educational conditions specifically effecting Muslims across the country. Need of the day calls for more data to be gathered pertaining to the situation of the Muslim community in order to effectively develop programs and influence policy-making that will promote the development and empowerment of Muslims in India. Additionally, this information would be of considerable value to NGOs seeking to work among Muslim populations.

Among the issues that have been subject to extended public debates and discussions in recent years has been the issue of ongoing marginalization and under-development of the Muslim communities in India. Though much has been written about various marginalized populations and the means by which empowerment has been pursued, little empirically-grounded research exists on the social, economical and educational conditions specifically effecting Muslims across the country. Need of the day calls for more data to be gathered pertaining to the situation of the Muslim community in order to effectively develop programs and influence policy-making that will promote the development and empowerment of Muslims in India. Additionally, this information would be of considerable value to NGOs seeking to work among Muslim populations.

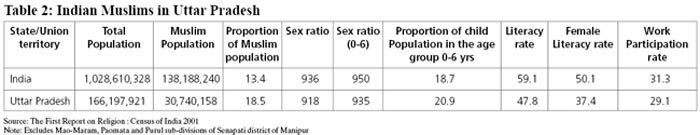

The most populous state of India, Uttar Pradesh, also bears the highest number of Muslim inhabitants. Muslims comprise roughly 20% of the state’s entire population. Specifically, the districts of Aligarh, Bulandshahr, Meerut, and Moradabad in western Uttar Pradesh have substantial Muslim populations, and were thus chosen as the areas this study has focused upon. While Muslims comprise approximately 35% of the population within these districts, this fact does not protect them from being the most deprived and marginalised group by all social and economical indices.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was two folds. In the first case, this study examines the social, economical and educational conditions of Muslims in the four deliniated districts, and to draw comparisons with other communities living in the same regions as well as comparisons with Muslims living elsewhere in the country. This includes the pursuit of a better understanding of the local, structural, and macro factors responsible for the relative deprivation of Muslims in the region and the identification of the causes of the deprivation and marginalization.

The second main thrust of this study was to identify local Muslim organizations and social activists working in these districts. This will enable NGOs and other like groups to establish links and develop joint activities for the empowerment of the Muslims in the area in an informed way. In relation to the above, this study also seeks to elicit the opinions of local Muslim groups about the felt needs of the community including which culturally appropriate methods of intervention are recommended for adoption by NGOs when working with local Muslim communities.

Major Research Questions

1. How do Muslims living in these four districts fare in terms of various social, economical and educational indicators?

2. How Muslims in these districts are placed vis-a- vis other communities in the region? What are the local and extra-local factors responsible for this difference?

3. How have a range of actors including politicians, and Muslim community leaders, as well as organizations such as the state bureaucratic system, and local NGOs responded to the fact of Muslim marginalization?

4. What sort of institutions and programs have local Muslim organizations developed to respond the need of community empowerment? What sorts of issues have they taken up? How effective have they been in pursuing their aims? What are the perceived drawbacks and difficulties faced? What primary needs do they see being felt by the community?

5. How do local Muslim organizations and social activists envisage the possibility of working with other NGOs to promote the development of the community? What culturally appropriate methods of intervention do they suggest?

Methodology and Research Design of the Study

This study has used both qualitative and quantitative methods of data gathering and has therefore utilized several instruments and techniques. The instruments used are as follows:

1 Questionnaires: Questionnaires have been used to collect data from households in rural as well as urban areas. They have also been used in the preparation of the village, town, and city profiles. The questionnaires have not only generated quantitative data but also provided qualitative data by eliciting the perceptions of people.

2 Interview Schedule: Numerous people were interviewed to capture their views on the subject matter under study.

3 Focus Group Interviews: In seeking to capture the views and perceptions of specific groups within the Muslim community, focus group interviews were used. This methodological strategy enhanced both qualitative and quantitative data. The focus groups were comprised of women, youth, unorganized sector labourers, professionals, and the elders of the locality, etc.

In addition, this study also has taken into account the following secondary sources: official government data and reports, existing academic literature and literature reviews, reports on the community by various civil servants and organizations. Further data was gathered from government departments including the National Minority Commission, and the government Census report, Newspaper reports, etc. round out the secondary sources consulted.

Scope of this study

This study reports upon and addresses the status of Muslims in four districts of Western Uttar Pradesh (Aligarh, Bulandshaher, Meerut, and Moradabad) as of 2009. The focus of this study takes into account the education and socio-economic situation of the Muslim communities in the area and examines the data for exclusions that may exist. The intended outcome of this study was to provide data and useful information to NGOs, individuals, groups, and Muslim communities in order to develop strategies and action plans for development, integration, and enhancement of the community.

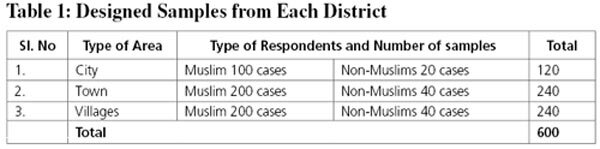

Designed Study Samples

Initially this study proposed to sample 100 Muslim households in each district identified. However, further data was gathered from non-Muslim households in each district, the need of which was determined by the researcher and indicated by the research objectives. This additional data served to situate the findings by providing contextually located comparisons with other religious groups living in the research area. Non-Muslim households comprised 20% of the total subject pool. The break-up of the 600 samples are given in Table 1.

The cities from which the data was collected were the district headquarters of each respective district. Within each city, samples were taken from 100 Muslim households and 20 non-Muslim households. The towns were chosen based on their substantial Muslim populations. The data in the towns sampled came from 200 Muslim households and 40 non-Muslim households. In terms of the villages, special care was taken in their selection and locations. Villages with high, mixed, and low Muslim populations were identified for sampling. The total number of individuals interviewed from such villages were 200 from Muslim households and 40 from non-Muslim households. Non-Muslim samples were taken from the “upper” caste, Dalit, and Other Backward Caste (OBC) households selected in accordance with the population percentage in the area. This was done in order to draw conclusions of comparative nature.

Sample Characteristics

In order to make the analysis comparative, both Muslim and non-Muslim residents living in the same localities were chosen. Of these respondents, 80% were Muslims and 20% non-Muslims. Of these, 18% of the respondents had been residing in the same locality between 1-10 years, 14% between 11 to 20 years, and 68% for more than 20 years. In terms of age, around 55% of the respondents were between 20 and 35, 36% were between 36 and 50, and the rest were between 51 and 66 years of age. As many as 65.8% of the respondents were males and 34.2% females. 28% of the respondents reportedly belonged to a caste categorised under OBC. It is possible that, some of the respondents hid their caste identity in order to pass off as belonging to a “higher” caste. Only 71% of the respondents possessed ration cards.

Apart from the sample survey, focus group discussions in selected villages and towns were conducted in order to collect qualitative information. Those participating in the focus group discussions included women, artisans, teachers, youths, and local leaders, etc. in order to provide the opinions of a broad section of the local Muslim community. Prominent personalities from the Muslim community of the selected districts were also interviewed and their perspectives on the issues affecting the community were recorded.

Challenges and Limitations of the Study

There were several challenges the researcher faced during the course of this study. First, it was difficult to convince the Muslim respondents of the study’s purpose and efficacy. Many were very suspicious of the study and some mocked it convinced that “this kind of research is not going to make any impact to say the least.” Respondents were not highly enthusiastic and instead were pessimistic about any outcome much less any help coming to them from our government agencies.

Another major challenge was the availability of reliable data or reports on the socio-economic and educational conditions of Muslims in general, and particularly with regard to the districts in Western Uttar Pradesh. However, a comprehensive literature review of the works which do exist has been incorporated in the report.

Various surveys as well as government reports have shown that, in the country, Muslims are among the most socially, economically, and educationally deprived communities under the categorization of religious minorities. Yet, little has been written on the social, economic, educational conditions, and other problems of India’s Muslims. A 2005 study conducted by the Action Aid and Indian Social Institute mentions following reasons for this:

1. Indifference or even hostility on the part of sections of the bureaucracy and the political classes to Muslim concerns. This is reflected in the fact that although statistics concerning Muslim education is collected by government agencies, the results are not generally made available to the public.

2. Lack of overall development of civic sense among Indians including, a lack of internalisation of the values, ethos, and directives enshrined in the constitution of India.

3. Indifference of many Muslim political leaders to the social, economic, and educational concerns of the Muslim masses. Like several of their Hindu counterparts, many Muslim leaders prefer instead to focus on identity related issues as these are considered more politically “rewarding.” This is also linked to the political interests of Muslim elites, many of whom, like their Hindu counterparts, appear to have a vested interest in preserving the status-quo.

4. Relative paucity of trained Muslim social scientists, owing, in part, to the relatively small Indian Muslim middle-class.

5. Indifference on the part of non-Muslim Indian social scientists in general to Muslim concerns, reflected in the few studies done by such scholars on Muslim related issues.

6. A strong tendency on the part of the press to present Muslims in a negative light by highlighting sensational stories or incidents relating to Muslims and ignoring their social, economical and educational concerns and problems.

7. Indifference on the part of the ulema (clergy), or Muslim clerics, and various Islamic organisations to the living conditions of the Muslim masses. This is reflected in their normative approach to Muslim social issues — particularly in their claim that social problems can only be solved by strict adherence to the shari‘ah, and that these need no special scrutiny outside the micro-lens of the religious tenets constructed by them. This explains why a few ulema Islamic organisations as well as Islamic publishing houses have not published any literature describing the actual social condition of the country’s Muslims. Instead, the overwhelming focus of the literature produced has been on religious or identity-related concerns, as narrowly defined, or on the history of Muslim ruling elites, with little or no attention being given to the living condition of the Muslim masses.

The study further documents that the existing literature on Muslim social, economical and educational issues is fairly limited in terms of both scope and quality. Much of these writings have been focussed on North India, leaving out other parts of the country where a significant number of Muslims live. Many of them are simply impressionistic and prescriptive, rather than descriptive. Few scholars writing on the subject have taken the trouble of doing empirical or field research themselves, relying instead on secondary sources including official reports and statistics. This naturally limits the value of such writings.

Sociological Context of the Muslim Problem

A look at the sociological and anthropological studies of Muslims in India in the past few decades reveals that general research interest has tended to focus on a few political areas and relegated the real problems to the background. The issues of vital importance have instead been explored through a lens of politicised Hindu-Muslim relations created by the essentialisation of religious identities (Faxalbhoy, 1997). This has resulted in a disincentive to understand the issues from a logical perspective and ameliorate the perpetual marginalisation and social exclusion of Muslims in India. The stereotyping of the Muslim “problem” is centred not only around bland and banal descriptions of social structures (Robinson, 1983: 97-104), but it also stems from various sociological and anthropological studies including studies on caste among Muslims (Lindholm, 1986: 61-73) of Muslims in general in South Asia (Madan, 1976), and of inter-Muslim interactions such Minault’s approach to the study of Islam in South Asia (Minault, 1984: 301-305). One study of the theoretical and empirical issues of sociological dimension is attempted by Imtiaz Ahmad and provides ample information on Muslims (Ahmad, 1972: 172-178). Further studies on the Muslims of Lakshadweep (Aggarwal, 1971) and on the Meos of Mewat Rajasthan round out the literature (Dube, 1969). The study on Mewati Muslims is interesting for its discussion of Muslim religious practices which have apparently included many Hindu rituals for over 300 years. Mewati Muslims became more committed to their Muslims identity after Partition.

To address issues of inequity and marginalisation, it is crucial to understand the reality of Islam in an Indian context. Muslims in India believe in and practice the cardinal pillars of the faith. Yet, the practice of Islam in India is heavily underlined “by elements which are accretions, drawn from the local environment and contradict the fundamentalist view of the beliefs and practices to which Muslims must adhere.” That is to say that there are at least two elements at work in Islam in its Indian context. “(One element is the) ultimate and formal (which is) derived from the Islamic texts, the other (is) proximate and local, validated by custom (Ahmad, 1981: 7-10).” This second or “other” element is what Arjun Appadurai has identified as a “gate- keeping concept,” namely, that third world societies are often studied with the help of “gate keeping concepts” or “theoretical metonyms,” i.e., concepts that seem to define the “quintessential and dominant questions of interest in (a) region (Appudurai, 1986: 356-361).” M. Gaborieau provides an example of this type of research in his study of Muslim bangle workers in Nepal. Gaborieau writes that Islam was only a “thin veneer” on Hinduism and the debate on caste among Muslims did not move out of the parameters set by caste hierarchy - which among Muslims is based on (the ashraf (noble)-ajlaf (inferior) distinction)(Gaborieau, 1984). While writing on conditions of Muslims in western UP, it is incumbent upon the researcher to keep pace with the empirical and theoretical framework of social science literature, studies of community identity, and various constructions of modality in order to theorize about current contemporary problems. Required is a dispassionate reading of contemporary history to locate the various causes leading to the present state of Muslims in India. Also required is an understanding of the complexity of the issues in order to engender appropriate corrective measures.

To address issues of inequity and marginalisation, it is crucial to understand the reality of Islam in an Indian context. Muslims in India believe in and practice the cardinal pillars of the faith. Yet, the practice of Islam in India is heavily underlined “by elements which are accretions, drawn from the local environment and contradict the fundamentalist view of the beliefs and practices to which Muslims must adhere.” That is to say that there are at least two elements at work in Islam in its Indian context. “(One element is the) ultimate and formal (which is) derived from the Islamic texts, the other (is) proximate and local, validated by custom (Ahmad, 1981: 7-10).” This second or “other” element is what Arjun Appadurai has identified as a “gate- keeping concept,” namely, that third world societies are often studied with the help of “gate keeping concepts” or “theoretical metonyms,” i.e., concepts that seem to define the “quintessential and dominant questions of interest in (a) region (Appudurai, 1986: 356-361).” M. Gaborieau provides an example of this type of research in his study of Muslim bangle workers in Nepal. Gaborieau writes that Islam was only a “thin veneer” on Hinduism and the debate on caste among Muslims did not move out of the parameters set by caste hierarchy - which among Muslims is based on (the ashraf (noble)-ajlaf (inferior) distinction)(Gaborieau, 1984). While writing on conditions of Muslims in western UP, it is incumbent upon the researcher to keep pace with the empirical and theoretical framework of social science literature, studies of community identity, and various constructions of modality in order to theorize about current contemporary problems. Required is a dispassionate reading of contemporary history to locate the various causes leading to the present state of Muslims in India. Also required is an understanding of the complexity of the issues in order to engender appropriate corrective measures.

Problematising Economic Marginalisation

At the dawn of the twentieth century, “Muslim(s) held approximately one-fifth of the land in the province. They tended to hold particularly large amounts around former centers of Muslim power such as Jaunpur, Allahabad, and Fatehpur, Bareilly and Moradabad, Lucknow and Bara Banki (Khalidi, 2006: 78).” According to official statistics, Muslims left as many as 14,221 bighas (portions) of land which was acquired by the custodian of Evacuee Property. This change in landed property indicates large-scale hardship within the Muslim community (Hosain, 1989:278-279). The passing of the Zamindari Abolition Act of 1951 deprived Muslims and other landed communities of all their land holdings except for that which they had kept unlet as “home farms” (sir and khudkasht) or as grove (bagh) land. In the words of Attia Hosain, “hundreds of thousands of families were faced with the necessity of changing habits of mind and living conditioned by centuries, hundreds of thousands of landowners and the hangers- on who had lost lived on their largess, their weakness and their follies (Please see, Id at 277).” Further, Muslim taluqdars were confronted with the stigma of having supported the creation of Pakistan as seen in the cases of Rajas of Jahangirbad, Kotwara, Mahmudabad, Nanpara, Salempur, and women like Qudsiya Aizaz Rasul. The stigma of association with the Muslim League hindered access to the centres of political power and influence (Robinson, 1993: 14-15), unlike in the case of the Hindu Zamindars (Jafri, 2004). In addition, the feudal ethos of high spending, low or no savings, conspicuous consumption and luxurious living further depleted Muslim wealth. The Zamindari Abolition Act did provide compensation spread over a number of years, however, installation amounts were often rapidly consumed leaving no savings. According to sociologist Zarina Bhatty, “Lacking power, their manoeuvrability was limited and consequently they lost a good part of their lands to the tenants who acquired legal rights over the lands that they were cultivating.

Socio-Economic Based Indicators

The NSSO’s 1987 survey which gathered socio-economic data from various segments of the Indian population failed to provide specific data on Muslim groups. Omar Khalidi however has produced a brilliant economic analysis of the marginalisation of Muslims in Uttar Pradesh. According to Ghaus Ansari, the vast majority of Muslims remained as landless labourers or engaged in various forms of manual semi-skilled labor as artisans who, contrary to popular and governmental perception, did not lag behind others in their craft (Ansari, 1960: 333). According to the Census report, “twenty-two percent of those earning a living from commerce were Muslims…. Muslims dominated trade in clothing, transport, hides, perfumes and luxury articles and played a large part in the food trade and others, though in spite of this they do not appear to have made much money (Census of India 1911).”

Of the skilled craftsmen, a 1991 survey gives the following figures: for embroidery (87.55%); cotton rugs (67.5%); zari, gold thread/brocade, and zari goods (89%); cotton rugs (67%); wood ware (72%) (Vijaygopalan, 1993: 9). Muslims’ specialisation in these crafts is exemplified by the cases of master weavers such as Pir Muhammad and Abdus Samad in Varanasi (Srinivas, 2002:94-96) for their silk sari, silk embroidery (Showeb, 1994), and zari (gold embroidery) (Showeb, 1993). Bhadohi and Mirzapur (Singh, 1979: M69-M71) are known for carpets, rugs, durries, and bed sheets. Kargha and handloom cloth are made in Mau. These weaving centres have held the monopoly on Muslim Julaha (weavers) and are based in Varanasi as well as other parts of eastern U.P. such as Azamgarh, Mubarakpur and Barabanki (Mehta, 1997). Hand printed textiles are made in Farrukahabad. The famed chikan (embroidered clothes) are associated with Lucknow (Weber, 1999). Jamdani (muslin/organza manufacture) is centred in Faizabad, zardozi (embroidery), and kalabattun (also called zari, i.e. gold thread) in Tanda. The Jhulan are also known as Momins/Ansaris (Pandey, 1983; PE19-PE28). In addition to weaving, there are other textile-related occupations in which Muslims are predominating: Dhuniya (cotton cleaners); Rangrez (dyers, tailors); Naddaf (fluffers), whose work is to rejuvenate the contents of quilts, pillows and mattresses.

In support of Muslim manufacture, Tahir Beg called for the “promotion of Muslim entrepreneurship under state support” to overcome constraints such as finance and marketing (Beg, 1993:223-236). Such an enterprise is already in the charter of the U.P. Minority Financial Development Corporation (UPMFDC) which was established in 1984 with a share of capital of 5 crore (UP Minorities). UPMFDC started the scheme, Margin Money Loan, under which a loan not exceeding 75% of a given project of up to Rs. 200,000 is given bearing 7.5 percent interest. In 1985/86 UPMFDC advanced a total sum of Rs. 8.24 lakhs to 47 units under this scheme (Ministry of Welfare, 1989: 121). The performance of UPMFDC in its two decades of operation, however, has not been satisfactory. Inquiry into the problems and issues deserves to be undertaken as part of a separate study.

It is clear that Muslim communities as a whole, as is shown, are among the poorest communities in India, ranking with the Dalits and Adivasis. And the economic marginalisation of Muslims can be attributed to numerous factors. These factors include 1) the fact that most Muslims in India are descendants of “low” caste converts, 2) the displacement and rapid marginalization of large sections of the Muslim elites with the onset of colonial rule, 3) the devastation of the community as wrought by Partition, 4) the abolition of zamindari which hit many Muslim landlords heavily, and finally, 5) the discriminatory practices perpetrated by the state and the wider Indian civil society in post-1947 India. These factors as well as more recent pogroms directed against Muslims have resulted in large-scale destruction of Muslim property and have further reduced the enthusiasm, security, and confidence that the community requires for economic advancement. Added to this is a lack of appropriate community leadership and the organisational mobilisation necessary to bring to light and work to address the social, economical, educational and political marginalisation of a large section of the country’s Muslims.

The above facts are highlighted in several studies that deal with India’s Muslims. Mohammad Zeyaul Haque’s article is based on the findings of the 55th round of the nationwide survey conducted by the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO — an autonomous body under the Union Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation). In it he writes that 29 percent of rural Muslims live in absolute poverty. Monthly per capita consumption expenditure for the rural Muslim poor is Rs. 300 or less. And, 51% of rural Muslims, as compared to 40% rural Hindus (including Dalits) are landless. In urban areas 40% Muslims, as compared to 22% Hindus, belong to the absolute poor category. Only 27% of urban Muslim households have a working member with a regular salaried job, compared to 43% among Hindus. As many as 48% of rural Muslims and 30% of urban Muslims are illiterate, and the corresponding figures for Hindus are 44% and 19% respectively.

Interestingly the research findings show that the housing conditions of Muslim households in rural areas is slightly better than that of Hindu OBC and Dalit populations, with relatively more Muslim families (30%) living in pucca houses than is typical in the general population (20%). One possible reason could be that many of these Muslim households have become poor only in recent generations owing to the distinct processes of Muslim marginalisation within India. Hence, while their present income may be low, their housing conditions are better. For the same reason perhaps, more than half of the rural Muslim household (56%) also have separate kitchens. Roughly the same proportion of all rural families, Muslim and non-Muslim alike, have electricity connections (about one in every eight households). Approximately one-fifth of rural Muslim households do not have ration cards, nearly all being from poor families.

In urban areas, economic differentials between Muslims and the general population are even wider than in rural areas according to the research findings. Ownership of a dwelling unit is less common among urban Muslim households (52%) than among the general population (78%). While 51.2% of Muslim households live in pucca houses, the figure is 57.3% for the general population. Only 87% urban Muslim households have electricity connections in their homes. The figure is around 95% for the general population. And around one fourth of the urban Muslim households are without ration cards.

Education Based Indicators

The research findings state that rural Muslim literacy rate in these districts is 36 percent, which is lower than the overall rate of 54 percent . The urban Muslim literacy rate is 49%, while for the general urban population it is 72.7%. Although Muslims are considerably behind other communities in terms of literacy, the study notes a progressive increase in Muslim school enrolment rates over the years, including female students, although the drop-out rate remains very high. Over half the Muslim students in both rural and urban areas study in government schools. Only two percent of rural Muslim students and 7.6% of urban Muslim students study in what the survey describes as “expensive private institutions.” The corresponding figures for what are termed “ordinary private institutions” are 15.7% and 24.6% respectively. About 24.1% of rural Muslim students and nine percent of urban Muslim students are enrolled in madrasas (Muslim religious seminaries). And as far as medium of instruction is concerned, 56.8% of rural Muslim students and 71.2% of urban Muslim students study in Hindi-medium schools, the corresponding figures for Urdu-medium and English-medium schools being 40.5%, 18.7%, 2.6% and 10.2% respectively. Interestingly, despite the fact that most students study in non-Urdu medium schools, 81% of rural Muslim students and 86.1% of urban Muslim students have learnt Urdu at school.

Educational Backwardness & Disempowerment and its Relationship to Employment

The economic marginalisation of Muslims in Uttar Pradesh has had direct bearing on the educational downfall which, in turn, has marginalised Muslims in terms of qualification for government jobs. Previously in the North Western Provinces and Oudh, Muslims enjoyed a greater percentage of the judicial and executive jobs than their numbers warranted. In 1882, Muslims held nearly 35% of all government posts (Supra note). In 1886, Muslims held 45.1% of the total number of posts in the judicial and executive services of the North Western Provinces and Oudh. In contrast, Hindus held only 50.2% of these posts, even though they constituted 86.2% of the total population (Misra, 1961: 329 & 388). With regard to employment requiring technical and applied scientific education, Sarojini Ganju has stated that, “they took hardly any advantage of the employment opportunities offered by the post office, telephone and telegraph services, and had little to do with the construction of roads and railways (Ganju, 180:279-298).”

One of the issues that must be considered is that the Muslim service class and the gentry had held aloof from modern education, for reasons of pride as self-perceived former rulers, religious taboos, fear of identity loss and the like. After an initial reluctance, Muslims did take to modern education, spurred by the efforts of Sayyid Ahmad Khan and his colleagues in the Aligarh movement (Mann, 1992:145-171). By the late 1860s, the proportion of Muslims in the government primary and secondary schools was as large as their percentage in the population and their percentage in higher education rose similarly by 1890s (Maqbool, 1969:5-6).

The downturn in education began with a bureaucratic reform initiated by U.P. Lieutenant Governor Anthony MacDonnell, a reform which resulted in adverse consequences for the Muslim elite. MacDonnell, “unlike his predecessors, who had treated Muslim landlords and government servants as pillars of British rule…developed a remarkable prejudice against them. He invariably described them as ‘financial’ and in times of Muslim agitation was sure that Muslim officers did not pull their weight. Muslims were a danger to security and their strong position in government services had to be reduced as far as was politically possible (Bhatty, 1973: 98).”

Further marginalisation followed with the Devanagri Resolution of 1990 which allowed the acceptance of petitions to the government in Devanagri letters. This in effect required that clerical appointments, since Muslims did not normally read the devanagri script, the new measure decidedly hurt Muslim interests.

Further marginalisation followed with the Devanagri Resolution of 1990 which allowed the acceptance of petitions to the government in Devanagri letters. This in effect required that clerical appointments, since Muslims did not normally read the devanagri script, the new measure decidedly hurt Muslim interests.

In the Post-independence era, Sardar Patel directed U.P. administrators to stop employing Muslims until the Muslim employment percentage was reduced to the community’s population percentage (Patel, 1998: 489-490). The Congress government led by Pandit Pant informed Vallabbhai Patel on May 28, 1947 that “according to the present practice and rule, 60% of the posts are reserved for Hindus, 30% for Muslims and 10% for others.” The Government proposed, regarding recruitment of Muslims for non-competitive posts, that all recruitment should be conducted purely on the basis of merit and fitness, regardless of communal considerations. The U.P. Hindu Mahasabha presented that, “as far as recruitment to government services was concerned… where selection is made otherwise than by competitive test, recruitment of different communities will be on the basis of population .” According to the former Aligarh Muslim University Vice-Chancellor Badruddin Tyabji:

There was a profound feeling of despondence and defeatism about these (employment) matters among the Muslim students in particular. Often without reason they considered it useless to apply for a job, being convinced in advance that they would not be selected (Tyabji, 1970: 35).

Muslim groups in U.P. frustrated with the result of the open competition hoped to be named “Other Backward Class,” in recommendation of the B.P. Mandal Commission in 1990. The demand for reservation was made forcefully with the support of the Congress Party, Bahujan Samaj party, and Samajwadi Party (Theodore, 1986: 1-8). One sample survey conducted by the Hamdard Education Society in 1983 indicated that Muslims felt the standards within their own institutions were far from rosy (Shah, 1985). Aijazuddin Ahmad shows a dismal picture: Muslim literacy rate is a mere 27%. Brij Raj Chauhan in 1992 stated that the “educational level of the members [Muslims] is not commensurate with their economic attainments and greater attention to the need for education has to be given for these groups (Chauhan, 1992: 54).” Ministry of Home Affairs sponsored a survey in 1981 of 45 districts in 12 states with large Muslim populations, including U.P. It revealed that Muslim enrollment and success in elementary, secondary, and high schools was poor. Nita Kumars’ work among the artisans of Varanasi shows an educationally depressed Muslim community with little interest in modern education (Neta, 1990: 82-96). The U.P. Rabita Committee’s 1992 survey of education in Aligarh discovered rampant illiteracy among the Muslim villagers in the districts of Aligarh and Bijnor (Islamic voice, 1992: 1&7). Naseem Zaidi says that “the low standard of Muslim pupils in the Aligarh district shows that a simple expansion of education alone is not enough to guarantee Muslim entry into high-paying jobs and professions (Zaidi, 1996).” In Aligarh Muslim University’s engineering, medical, and other professional schools, Muslim students form a slim majority due to the minority character of the institution, though officially there is no reservation of seats for students along religious affiliation. The decision of AMU to reserve 50% of seats in MD, MS and some post-graduate courses for Muslim students from all parts of the country, and split the resulting 50% between an “all India quota” (25%), and AMU’s internal students (The Milli Gazette, 2005: 2) was endorsed by then Union Ministry of Human Resource Development, and opposed by Sangh Parivar, and CPI-M associated faculty members. In a case, the reservation policy of the University was struck down by the Allahabad High Court in 2005 (Wright, 1996:1-2).

Issues related to Muslim education appear to have received somewhat more attention by writers and scholars than the question of Muslim economic conditions. However, writings on Muslim education are of uneven quality. Many such writings are simply historical accounts of Islamic education or of educational reformist movements that spawned the colonial period, such as the Aligarh school and the Deoband madrasa. As in the case of current writings on Muslim economic conditions, the quality of writings on contemporary Muslim education in India leaves much to be desired. There exist only a few studies on this subject that are grounded in rigorous field-level observation and research.

M. Akhtar Siddiqui argues that in the aftermath of the Partition, education among Muslims suffered a tremendous set-back. With the dissolution of princely houses and feudal estates, the patronage on which numerous madrasas had depended evaporated (Siddiqui, 2004). To make matters worse, discriminatory policies were adopted by the state vis-à-vis Urdu as the language of instruction. Siddiqui shows how Muslims have sought through novel experiments to maintain and promote the tradition of Islamic education in the face of tremendous challenges. For instance, in Uttar Pradesh, in response to the marked Hinduisation of the government school syllabus and the numerous negative references to Islam and Muslim personages in government-prescribed textbooks, the Dini Ta‘limi Council established a number of maktabs which combine religious and secular education as well as Urdu until the fifth grade and allow their students to join government schools thereafter.

Siddiqui sees the state’s discriminatory policies vis-à-vis the Urdu language as one of the major reasons for Muslim educational backwardness, particularly in North India. However, he argues that while Urdu is “an important element” of Muslim identity, it is wrong to identify the language as “Muslim” even though today, for all practical purposes, non-Muslims have abandoned it. And as a result, the teaching of Urdu is today restricted largely to madrasas. This is one reason why many Muslim families prefer to send their children to madrasas instead of schools. In the Urdu “heartland,” Uttar Pradesh, Urdu today is languishing, dying a slow death, as reflected by the fact that few Urdu medium state schools are left in existence. This is a gross violation of the Constitutional right of Muslims to be taught in their own mother tongue. The situation is considerably better, however, Siddiqui points out in states beyond the Hindi-Urdu belt, such as Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, where state governments have funded several Urdu schools, although their standards are said to leave much to be desired.

Another study by Sekh Rahim Mondal argues that the educational backwardness of Muslims in India should be understood in the wider context of their overall socio-economical and political marginalisation (Mondal, 1997). Being a vulnerable minority, Muslims feel their identity and lives are under threat, which enhances the influence of the orthodox and conservative ulema, who are generally known for their lack of enthusiasm for “modern” education. Further inhibiting educational advancement of the community is the fact that many Muslims are engaged in “marginal” economic activities that do not require “modern” education. This, in addition to widespread poverty among Muslims, limits their levels of educational aspiration. In addition, the fact mentioned earlier that many Muslims are descendants of “low” caste converts who have retained many of their pre-conversion beliefs and practices, and further, have remained mired in poverty like most other “low" caste people, makes higher education an unaffordable expense for many. Making the situation more complicated has been the mass migration of the North Indian middle-class to Pakistan following Partition. The loss of those who could have been expected to take leading roles in the promotion of modern education in the community has been substantial.

Studies on Muslim education which have looked at both madrasa as well as “modern” education have found that, contrary to widely-held stereotypical notions, only a very small percentage of Muslim children of school-going age attend fulltime madrasas to train as religious specialists or ulama. Considerably more children study in part-time maktabs or mosque schools, while receiving education in regular government or private schools as well. Maktabs exist in almost every locality where Muslims live and play a crucial role in transmitting the Islamic tradition to the younger generation. These institutions have the potential to promote literacy and some degree of modern education, although, in many cases this potential does not seem to have been taken advantage of in any noticeable way.

Education and Muslim Women

The literacy rates of Muslim women are among the lowest in the country. Several studies have sought to explore the reasons for this fact, particularly by looking at parental attitudes. An interesting work in this regard is Hafiz Abdul Mabood’s “A Study of Attitudes of Teachers and Parents of Azamgarh District Towards Muslim Girls’ Education (Maboob, 1993).” This study was based on a sample of 70 Muslim teachers in government and government-aided schools and madrasas in the Azamgarh district in eastern Uttar Pradesh as well as on the parents of students studying in these institutions. The study began by noting that while male literacy was fairly high among the Muslims of Azamgarh, the female literacy rates were very low. The aim of the study was to discover why this is so by focusing particularly on attitudes towards Muslim women’s education. What it found was that almost all the madrasa teachers surveyed believed in the importance of girls’ education but stressed that the ideal education which Muslim girls should receive should be religious in nature. Additionally, a modicum of general subjects that enable girls to become good housewives and mothers was considered ideal as well. Eighty percent of parents believed that as far as religious education is concerned, there should be no distinction between boys and girls. Some of them allowed girls to study in schools, but stressed that for these girls to be educated, they must study in all-girl schools and under female teachers, and ultimately, they must discontinue their studies after the attainment of puberty. Further, it was deemed imperative that these schools be located within the locality where the girls live.

Muslims’ Perspective on their Own Plight

Data from the Focus Groups

Focus group discussions were organized to supplement the data generated through secondary sources and questionnaires, for the purpose of this study with selected members of the local Muslim communities under research. The intention was to bring out qualitative information that cannot be fully gleaned through questionnaires and is not adequately dealt with in the available secondary literature. These discussions brought out a number of common issues, indicating common trends across all four districts.

A major point was repeatedly stressed in all group discussions: that the government institutions are, by and large, indifferent, if not hostile toward the Muslim community. The point was repeated by all — men, women, and social activists — in individual conversations and interviews. The indifference and hostility on the part of government institutions was attributed to anti-Muslim prejudice and to the growing influence of Hindutva propaganda against Muslims. Comparisons were drawn between Hindu and Muslim localities to stress the point that the latter are much more deprived than the former in terms of government expenditures on various developmental schemes. It was pointed out that basic infrastructure and local facilities, such as proper roads, sewage systems, banks, dispensaries, health clinics, schools etc. were largely conspicuous by their absence in most Muslim localities. Some of the participants in cities claimed that while they, like others, are also tax-payers, they are consistently ignored by government departments. Even in Muslim majority areas it was pointed out, there are hardly any Muslim employees in government departments, even in junior posts such as drivers, cleaners, and clerks, for which higher educational qualifications are not required.

A major point was repeatedly stressed in all group discussions: that the government institutions are, by and large, indifferent, if not hostile toward the Muslim community. The point was repeated by all — men, women, and social activists — in individual conversations and interviews. The indifference and hostility on the part of government institutions was attributed to anti-Muslim prejudice and to the growing influence of Hindutva propaganda against Muslims. Comparisons were drawn between Hindu and Muslim localities to stress the point that the latter are much more deprived than the former in terms of government expenditures on various developmental schemes. It was pointed out that basic infrastructure and local facilities, such as proper roads, sewage systems, banks, dispensaries, health clinics, schools etc. were largely conspicuous by their absence in most Muslim localities. Some of the participants in cities claimed that while they, like others, are also tax-payers, they are consistently ignored by government departments. Even in Muslim majority areas it was pointed out, there are hardly any Muslim employees in government departments, even in junior posts such as drivers, cleaners, and clerks, for which higher educational qualifications are not required.

Some of the participants stressed that the neo-liberal economic policies being followed by successive governments in the last two plus decades have hit Muslim artisan communities, such as the potters of Khurja, weavers of Meerut, and craftsmen of Muradabad and Aligarh badly. The policies have resulted in the further economic marginalization of these communities. Linked to this, the cutting back of subsidies and the privatisation of education have made quality education even more difficult for these communities to gain access to. Yet, the government has done little to address the situation. Further, many respondents argued, in areas where Muslims have witnessed some degree of upward economic mobility, often anti-Muslim riots are engineered by Hindu chauvinist groups in league with agencies of the state resulting in tragic loss on a massive scale of Muslim lives and property. Hence, the government, they argued, is to a large extent responsible for the marginalization of Muslims.

In focus group discussions, another salient point was that most respondents felt that Muslims, as a whole, were economically far behind Hindus, particularly “upper” caste Hindus. In light of this, they offered various suggestions, such as greater state allocation in various development schemes slated for Muslim areas. Further it was suggested that a separate reservation for Muslims as a whole, or for Backward Caste Muslims in specific, be created for various government jobs and educational institutions. They also repeatedly stressed the point that Muslim economical and educational development hinges crucially on the communal situation in the country. Hindutva fascist forces, they argued, could not tolerate Muslim development — neither economically nor educationally. They claimed that Hindutva groups wanted to convert Muslims into the “new untouchables” by engineering periodic pogroms directed against them, by ignoring them in government development projects, and by branding all demands as “communalism” (such as the demand that the state must address the economic plight of the Muslims). In fact, some of them argued, Muslims who before 1947 had a fairly sizeable presence in government service, now lag considerably behind Dalits in this sphere.

Some “low” caste Muslim respondents pointed out that while their castes had been included in the official list of Other Backward Castes, they had not benefited from this provision. Government facilities for the OBCs, they said, had been cornered almost entirely by more numerous and influential Hindu OBCs. Some of these respondents argued that the Presidential Order of 1950 extending Scheduled Caste status only to Hindu Dalits (later extended to Sikh and Buddhist Dalits as well) was unconstitutional and anti-secular. For this Order had resulted in the further marginalization of Dalit Muslims, who are not eligible to apply for various schemes of the state reserved specifically for the Scheduled Castes. Consequently, they said, the economic and educational condition of Muslim Dalits was considerably worse than their non-Muslim counterparts. Hence, they insisted, the Presidential Order of 1950 needs to be amended and Dalit Muslims must also be treated by the state as a Scheduled Caste.

Several Muslim respondents also lamented what they referred to as the government’s consistent discriminatory policies vis-à-vis the Urdu language. This, they argued, was also a significiant reason for their economic and educational backwardness. It is the fundamental right of all communities, they said, to receive instruction in their own mother tongue. But through various anti-Urdu policies, the government had, they claimed, subverted this right for Muslims, many of who consider Urdu their first language. They described the government’s policy towards Urdu as a sign of anti-Muslim prejudice and at the same time pointed out that it was misleading to consider Urdu as a specifically “Muslim” language. In Uttar Pradesh, once considered the bastion of Urdu, they pointed out, there were few to no facilities for children from Urdu-speaking families to educate their children in Urdu-medium schools beyond the primary level. Instead, children were forced to learn Hindi and Sanskrit. Thus, by effectively marginalizing Urdu and, by de-linking Urdu from employment opportunities, the state had, they insisted, only further exacerbated the problem of an already marginalized Muslim education. To add to this, they pointed out, government-approved textbooks often contain negative portrayals of Islam and Muslims and are heavily laced with stories from Hindu religious texts. The type of nationalism the government seeks to inculcate in Indian students through textbooks and school activities, such as compulsory prayers etc., is also heavily Hinduised. Many respondents were critical of this, and expressed a suspicion that this was part of a carefully calculated effort to “de-Islamise” Muslim children, to “Hinduise” them as well as promote anti-Muslim feelings among non-Muslim students. Because of this, they said, some Muslim parents are reluctant to send their children to school to study.

In terms of education for women, women as well as men were critical of conservative Muslim religious leaders, alleging that they had wrongly confused patriarchy with Islam. Due to strict purdah, it is difficult, they said, for many Muslim women to acquire education. As a result Muslim women are forced to remain “ignorant.” To promote Muslim women’s education, they stressed the need for the state and the community to devote more attention and resources to setting up separate girls’ schools and colleges.

Growing Hindu fascism was and continues to be another concern. In many villages where interviews and focus group discussions were held with Muslims, the relations between Hindus and Muslims were fairly cordial. In several villages, traditional bonds were still intact and Muslims and Hindus attend each others’ functions. Yet, several other villages covered in this research, and particularly the towns and cities, presented a different picture. Respondents in these areas spoke of the presence and growing influence of Hindu right-wing groups, particularly through shakhas and schools run by various entities such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, visiting pracharaks, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Dal, and the leaders of various political parties. They pointed out that there have been too few organised initiatives to combat these forces, and many expressed the fear that if they continued unchecked, Muslims might face a similar situation as their co-religionists in Gujarat during the state-sponsored anti-Muslim violence of 2002. This, they felt, called for urgent steps to address the phenomenon of growing Hindutva fascism.

The role of the media also came into question. In several places, respondents pointed out that although violent communal incidents had not taken place in their own localities, many Hindus and Muslims have negative images of each other. These notions they see as having been and continue to be reinforced by the media and politicians as well as communal groups. They stressed the need for steps to be taken both by the state as well as civil-society organizations to promote inter-community dialogue. Some respondents also expressed the view that the ulema were, in part, to blame for not playing an active role in promoting better relations between Muslims and others and by reinforcing their own negative stereotypes about other communities.

The role of the media also came into question. In several places, respondents pointed out that although violent communal incidents had not taken place in their own localities, many Hindus and Muslims have negative images of each other. These notions they see as having been and continue to be reinforced by the media and politicians as well as communal groups. They stressed the need for steps to be taken both by the state as well as civil-society organizations to promote inter-community dialogue. Some respondents also expressed the view that the ulema were, in part, to blame for not playing an active role in promoting better relations between Muslims and others and by reinforcing their own negative stereotypes about other communities.

In terms of Muslim leaders, while critiquing the government as well as Hindu chauvinist organizations and blaming them for many of their problems, many respondents were also very critical of the existing Muslim community leadership. In support, several respondents argued that the ulema of the madrasas were serving the community by promoting religious awareness and preserving Islamic identity and the tradition of Islamic learning. The madrasas, they said, were also playing an important social role by providing free education and boarding and lodging facilities to many Muslim children from poor families, victims of governmental neglect. Yet, they pointed out, the ulema needed to widen their horizons, play a more active role in the economical, social and educational development of the community and refrain from promoting sectarian strife. Some respondents critiqued the ulema for not being able to offer what they called a “proper” interpretation of Islam attuned to the context of contemporary India, and because of this, they feel that Muslims and Islam had gotten a “bad name.” They also stressed that the distinction that many ulema make between “religious” and “worldly” knowledge is “un-Islamic” and said that this had contributed to further educational backwardness in the community.

Similarly, many respondents were critical of Muslim politicians for not raising the vital issues of economical, social and educational empowerment. They accused the Muslim political leaders of being in league with Hindutva chauvinists and the state machinery in promoting communal controversies, which they feel results in the perpetuation of the poverty of the majority of Muslims. Most Muslim political leaders, they said, were simply “agents” of various political parties who use Muslims as “vote banks” but do little, other than adopting some cosmetic measures, for the Muslim masses. They suggested the need for an alternative Muslim leadership that focuses on the social, economical and educational problems of the community and abstains from unnecessary communal controversy. They stressed the need for community leaders to form liaisons between state agencies and the community so that the public could access information regarding various government developmental schemes. They also called for Muslims politicians to set up more non-government agencies for community development as well as to create more meaningful and significant interactions with secular NGOs.

Major Findings

Urban Areas

This research revealed that a very large proportion of the respondents live in very dismal economic conditions. Reportedly, 32% stated an annual household income of less than Rs.10,000; 26% between Rs 10,001-Rs.20,000; 14% between Rs. 20,001-Rs.30,000; 6% between Rs.30,0001-Rs.40,000; 8% between Rs.40,001-Rs.50,000; and 14% above Rs.50,000. Another indication of the poor economic conditions of most of the respondents is the fact that 74% of Muslim children do not receive any sort of financial aid for education. A lack of awareness of the financial aid schemes for education instituted by the government is evident from the fact that 56% reported that they are not aware of such schemes.

All the respondents were asked to report as to which medium of instruction was followed in the schools their children attend. The data shows that 74% of respondents send their children to study in Hindi-medium schools, 7% in Urdu-medium schools, and 19% in English-medium schools.

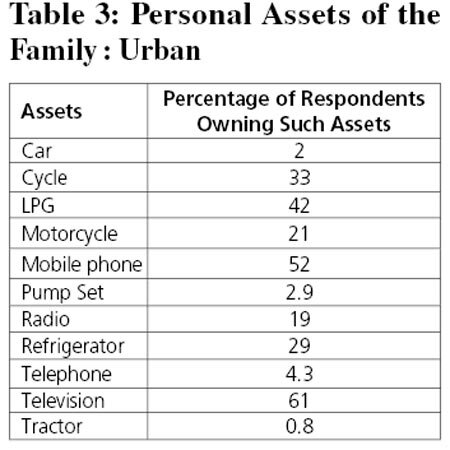

In terms of housing, of the total respondents, 54% live in regular houses, but a significant 21% live in jhuggis in the slums, and 23% in rented accommodations. 46% respondents live in one-room houses, 29% in houses with two rooms, 13% in houses with three rooms, and 12% in houses with four rooms. Table 3 provides further details of the economic conditions of the respondents based on ownership of various assets.

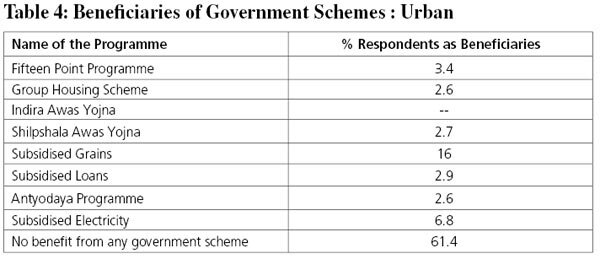

Though the government welfare schemes exist, only a small proportion of respondents had benefited from various development schemes of the state, indicating that Muslims, by and large, do not receive the attention they deserve by the state development planning and implementation authorities. This fact is evident from Table 4.

In terms of health care, given the relatively high incidence of poverty and marginalisation among the respondents, it was found that a substantial proportion of them cannot afford expensive private medical treatment. Consequently, 46% reported going to government health centres and hospitals for medical treatment and the rest have been left to the mercy of private registered allopathic and homeopathic practitioners. A striking 67% reported that they did not have access to free medical care. Considering the high levels of poverty among the respondents, it is worth noting that 28% respondents spend up to Rs. 5000 every year for the medical treatment of their family.

In terms of health care, given the relatively high incidence of poverty and marginalisation among the respondents, it was found that a substantial proportion of them cannot afford expensive private medical treatment. Consequently, 46% reported going to government health centres and hospitals for medical treatment and the rest have been left to the mercy of private registered allopathic and homeopathic practitioners. A striking 67% reported that they did not have access to free medical care. Considering the high levels of poverty among the respondents, it is worth noting that 28% respondents spend up to Rs. 5000 every year for the medical treatment of their family.

In all selected districts 79% respondents claimed that the Below Poverty Line (BPL) survey was not done sincerely, leaving out many people who were living below the poverty line. The exclusion of poor families does not just amount to manipulating the regional or national data but it also deprives poor families of whatever meagre assistance they are entitled to from government sources. This clearly allows for the further marginalisation of an already marginalised people in an unhindered manner. In such a situation as this, where the survey among the marginalised was deliberately undertaken in a less than sincere way, most respondents, as expected, did not have a BPL card. In fact, an alarming 22% of respondents claimed that they do not possess BPL cards although they qualify for the same.

The trend suggests that the Muslim-dominated localities in the cities tended to be neglected in terms of civic amenities and government infrastructure. 53% of respondents said that their locality did not have adequate street-lighting, 69% said they did not have proper sewage facilities and 39% said they did not have access to a municipal water supply. 88% of respondents claimed that there were no municipal garbage dumps in their locality, and only 27% said that the condition of the roads in their area were good.

Though most of the areas from where the respondents were chosen for the interviews were Muslim dominated, 64% of the respondents said that their area councillor was non-Muslim. Ideally, the interaction between citizens and their elected representatives forms the bedrock of any democratic structure. However, 69% of the respondents expressed that to get their problems heard and addressed was difficult. Though questions as to why respondents found it difficult to approach their elected representatives was not included in the schedule, it can be conjectured that the religious barrier may well be one of the reasons responsible for the distance between the people and their elected representatives.

Overall, Muslim localities in urban areas are considerably marginalized and discriminated against in terms of government resource allocation. This is particularly alarming given the fact that, and as the figures presented above show, the majority of urban Muslims are engaged in low-paying professions and display a high level of illiteracy. The problem is exacerbated by the absence of effective local leaders able to work with local level government officials to help implement development schemes. This calls for state authorities to pay special attention to infrastructural development in Muslim localities, and also, for Muslims themselves to organise and channel resources for community development along side agencies of the state.

In terms of schemes already in effect, in the low annual income group of up to Rs. 20,000 we do see that there are some beneficiaries of government schemes. But even amongst these low income groups more than 80.0% of the respondents claimed that they are not benefiting in any way from this scheme. Overall this deprivation is 85.6%, which simply denotes that the scheme has failed miserably.

Indira Awas Yojana is a government scheme aimed at providing houses to the poor. It has also failed miserably. Only 1.2% of respondents in the annual income group of up to Rs 10,000 accepted that they have benefited from this scheme. In the other income categories this deprivation is more than 99.0%. In the income group of Rs. 40,000 and above this deprivation is an absolute 100.0%. This scheme was initiated to help families in distress by providing loans at a subsidized rate. The total percentage of beneficiaries across the income groups has been less than one percent. In other words, 99.1% of the respondents have never benefited from the subsidized loan schemes.

As with the other government schemes, the Antyodaya scheme also failed to make any impact amongst the population surveyed. Only 1.3% of the respondents across the income group accepted that they are benefiting from Antyodaya. 98.7% of the surveyed families replied that they have not benefited from this scheme at all.

Providing electricity at subsidized rates is yet another government scheme which has failed to make any impact on the surveyed population. More than 97.0% of those surveyed replied that they are not getting any subsidized electricity. The total percentage of beneficiaries across the income groups was just 2.8%.

The 15 point program is another ambitious program of the government, which was aimed at the minorities including Muslims for their all-round development. But this program has failed to make any impact on the lives of the people it has targeted, as our findings suggest. The number of beneficiaries from this program was just two percent. It was very disappointing to note that a program which was meant for the minority community has not been implemented properly.

Rural Areas

Of the rural populations sampled in this study, 38% live in Muslim-majority villages, 22% in villages with a roughly equal Muslim and non-Muslim population, and 30% in villages where Muslims form the minority. Research data reveals that in most parts of rural Muslims are associated with low status occupations, and have on average less landholdings than other communities, particularly “upper” caste Hindus. As in urban areas, many Muslims in rural areas complain of discrimination as well as indifference and neglect by government authorities. This marginalisation has been well reflected in the occupational structure of Muslims living in rural areas. 39% of respondents identified themselves as farmers, 17% as agricultural labourers, 12% as casual unskilled labourers, eight percent as skilled labourers, three percent as self-employed professionals, four percent as self-employed small businessmen, 0.4% as self-employed artisans, 12% as domestic or household workers, 0.8% as government servants, and 4.3% as private sector employees.

The study further reveals that the high degree of rural Muslim poverty is evidenced from the fact that 42% respondents have a total annual household income of less than Rs. 10,000; 17.5% between Rs. 10,001-Rs. 20,000; 5.4% between Rs.2 0,001-Rs. 30,000; and only 0.1% between Rs. 30,0001-Rs. 40,000. Other indices provide additional evidence of substantial rural Muslim marginalisation. 85% of children study in Hindi-medium schools, nine percent in Urdu-medium schools, and six percent in English-medium schools.

As in urban areas, many rural Muslim families complain of being deliberately neglected in government programmes meant for the alleviation of rural poverty. This fact was brought to light by the majority of respondents who said the identification of poor families for the BPL survey had not been conducted in their village. In fact, a startling 74% of the respondents said that their community had not benefited at all from schemes. Several reasons were offered for this, including dishonest implementation by officials and gram panchayat representatives, anti-Muslim prejudice, the poverty and illiteracy of most Muslims, lack of awareness of schemes, and also reluctance to take advantage of government schemes or indifference thereto. Further, relatively few Muslims appear to have access to institutional forms of credit. Only nine percent respondents have taken credit in the case of emergency from a bank. 20% generally take loans from moneylenders. 21% from relatives, 13% from neighbours and one percent take loans from credit societies.

Local institutions such as panchayats play an important role in mediating and solving conflicts, including conflicts between members of different castes and religious communities. However, given the fact that these institutions are generally controlled by those from “upper” castes — often “high” caste Hindus — that role often is not fulfilled. It appears that a significant number of rural Muslims do not have or are denied proper access to panchayat institutions. Thus, 93% of the respondents said that they had not participated in any gram sabha meeting in the entire previous year.

Overall, therefore, as these figures indicate, it appears that a significant proportion of rural Muslims have been deliberately or otherwise marginalised and left out of the development process. The deleterious impact of globalisation and neo-liberal economic policies on vulnerable rural communities is obvious, and in particular, many rural Muslim families have been hit severely by these. These findings call for the state as well as civil society organisations to take a more pro-active role in addressing the specific concerns of rural Muslim groups, and making special efforts for developing and implementing various social development schemes.

Conclusions

Muslims in four districts of western Uttar Pradesh, like other parts of the country, have faced severe marginalisation. There is no question about this. Through governmental and social actions, substantial prejudice based on fundamentalist activities, and active stereotyping in numerous mediums the Muslim community has been repeatedly marginalised within India. This has had the effect of producing a great deal of hardship for the Muslim community in India. Further, the literature documenting Muslims in India has not served to reverse these problems or take the community forward toward socio-economical and educational well being. In fact the majority of studies in the past have addressed issues of religion instead of economical and educational marginalization; they have reinscribed the tendency toward sectarianism and distance between communities rather than provide information which productively neutralizes the marginalisation and prejudice against this, the country’s largest minority group. Admittedly, there has been a dearth of written material to begin with, and this study puts forth a clear call for research that provides law makers, civil servants, and organizations with the information they need to effectively put into place programs which support and uplift all of the country’s citizens who are in need. Such research is particularly needed on as well as from the Muslim population.

Even more importantly though, the conclusions of this study put forth the call for immediate social action. By gathering data on the economic and educational standing of Muslim populations in Uttar Pradesh, this study has served to produce data and materials of practical use for a variety of organizations. The statistical data resulting from this study proves without a doubt that Muslim communities are suffering from a lack of economic and educational rights. And not just rights - of which rectification and implementation is the purview of the law, its makers and enforcers — but a lack of actual materials i.e. jobs providing a reasonable level of income, health care, quality education, dependable infrastructure, and so on. This study has taken as its main quantitative focus the economic and educational needs of the community. And necessarily so for it is clear that there is an interactive connection between the two; one cannot be addressed nor redressed without the other. The necessity of social action which can address the myriad of needs that fall under these two categories is clear, and suggestions for such action follows below. Of the qualitative data from this study, what has been shown is that Muslims feel neglect and even hostility from the structural and social power centers of the country. Clearly stated is the need for governmental policies that, rather than hinder, accomplish the goal of assisting the community. Also clearly voiced is the call to monitor and, if needed, moderate the rise of Hindu fundamentalism, particularly when state involvement is present. Further, the rehabilitation of Urdu as an Indian language is indicated as opposed to the current practice of reducing Urdu to a mere “Muslim” language and then using it as a marginalising agent against the community. The cessation of Muslim vilification in school materials, and more respect for the issues involved in creating effective women’s education are also indicated. Clearly, these are just a few of the issues that this study has gathered data around. Clearly action redressing all that this study has presented and more is of vital importance if the Muslim segment of India’s citizens are to move forward not only toward equality but empowerment with the rest of this great nation.

Suggestions for Social Action

Overall, as the findings of this research suggest, Muslims are amongst the most marginalised communities in the area in terms of economic and educational indices and also in terms of political empowerment. The study endorses the findings of other studies on the Muslim community as discussed above. It also shows that the situation of Muslims is quite similar to those of Dalits. Evidence suggests that like Dalits the Muslims are treated like second class citizens and socially discriminated against.

A sense of insecurity and exclusion persists in Muslim communities in varying degrees and has increased considerably in the 1990s — especially after the demolition of the Babri mosque at Ayodhya followed by violence against Muslims in Gujarat. The acts of fundamentalist forces from the dominate community have strengthened the stranglehold of the obscurantist elements over the minority Muslim community. Thus, the prospects of development and progress have been further minimised for a community already dogged by poverty and educational backwardness.

The data reveals backwardness among Muslims on many counts. It shows that there has been a serious lack of attention to the condition of the Muslim community by various actors, but more so, by the State over the last six decades. The Muslims have lagged behind at all fronts, concerning socio-economic factors both in rural and urban areas. Although the factors responsible can be numerous from within and outside the community. There is no denying the utter failure of the state in the largest democracy in the world to provide a conducive environment for growth and development to its largest minority. These facts cannot be ignored by the state, the policy-makers, civil society, or the Muslim leadership.

A host of factors, as the study points out, have been responsible for the marginalisation of Muslims and thus the situation calls for urgent steps to remedy the situation and ameliorate their condition educationally, economically, socially and politically. Communal violence, generally, has severely affected Muslims more than any other minority group. Various reports suggest that it is Muslims who bear the brunt of the violence in terms of loss of life and property, displacement, and a denial of justice. The violence adversely affects the education of children, income and livelihoods, the health of women and children, and social life in terms of mobility and quality of interaction.

The socio-economical backwardness, educational deprivation, political marginalisation and exclusion of Muslims from the mainstream development processes seems to be structural and linked to policy decisions, failed implementation, and the general apathy of a large section of society — politicians, bureaucrats, police persons, and civil society.

Reference and Additional Thinking

- (1985): ‘UP Minorities Finance and Development Corporation’, Muslim India, pp 34, 41.

- Aggarwal, P. (1971): ‘Caste, Religion and Power’, New Delhi: Shri Ram Centre for Industrial Relations.

- Ahmad, Aijazuddin. ‘Muslims in India’, Vols 1-4, New Delhi: Inter-India, 1993-96.

- Ahmad, Imteyaz. (1972): 'For A Sociology of India', Contributions to Indian Sociology, 6, pp 172-178.

- Ahmad, Imteyaz. (1981): ‘Rituals & Religion Among Muslims in India’, pp 7-10

- Ansari, Ghaus. (1960): ‘Muslim Castes in Uttar Pradesh’, Lucknow: Ethnographic and Folk Culture Society.

- Appadurai, A. (1986): 'Theory in Anthropology: Centre and Periphery', Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol 28, pp 356-361.

- Armanullah: ‘A Study of Problems and Performance of Muslim Entrepreneur in Handloom Industry of Gorakhpur’, unpublished M.Phil thesis, Aligarh Muslim University.

- Beg, Tahir. (1993): ‘Promotion of Muslims Entrepreneurships under State Support’, pp.223-236, in Aspects of Islamic Economics and the Economy of Indian Muslims, edited by F.R. Faridi, New Delhi: Institute of Objective Studies

- Bhatty, Zarina. : ‘Status and power in a Muslim-Dominated Village of Uttar Pradesh’, p.98, in Caste and Social Stratification Among

- Bhatty, Zarina. (1973): ‘Status and power in a Muslim-Dominated Village of Uttar Pradesh’, in Caste and Social Stratification Among the Muslims in India, edited by Imtiaz Ahmad, New Delhi: Monohar, p.98.

- Census of India:1911: UP Part I p.333

- Chanuhan, Brij Raj. (1992): ‘Rural-Urban Interactions of Muslims in Meerut Region’, : ICSSR, p.54

- Dube, L. (1969): ‘Matriliny and Islam: Religion and Society in the Laccadives’, National, Delhi.

- Fazalbhoy, Nasreen. (1997): Sociology of Muslims in India: A Review; Economic and Political Weekly, June 28.

- Gaborieau, M. (1984): 'Life Cycle Ceremonies among Muslims in Nepal and Northern India' in Y Friedmann (ed), Islam in Asia, Vol 1, South Asia, Magnes Press, Jerusalem.

- Ganju, Sarojni. (1980): ‘Muslims of Lucknow, 1919-1939’ in Kenneth Ballhatchet & John Harrison, The City in South Asia: Pre-Modern & Modern, 279-298.

- Haque, Mohammad Zeyaul. : ‘The “appeased” Indian Muslims are far more deprived’ (http://www.milligazette.com/Archives/01102002/0110200297.htm).

- Hosain, Attia. (1989): ‘Sunlight on a broken Column’ (New York: Penguin-Brooks Virago Press, first published in 1961), pp. 278-279

- Islamic Voice, (1992): ‘Rampant Illiteracy among Aligarh Muslim Villagers’, pp. 1&7.

- Jafri, S.S.A. (2004): ‘Socio-Economic Condition of Downtrodden Minorities in Lucknow Metropolis’, Lucknow: Giri Institute of Development Studies.

- Khalidi, Omar. (2006): ‘Muslim in Indian Economy’, Three Essays Collective, 1st Edition, p 78

- Kumar, Nita. (1990): ‘the “Truth” about Muslims in Banaras: An Exploitation in School Curricula and Popular Lore’, Social Analysis 28: 82-96

- Lindholm, C. (1986): 'Caste in Islam and the Problem of Deviant Systems: A Critique of Recent Theory', Contributions to Indian Sociology, (ns) Vol 20 (1), pp 61-73.

- Mabood, Hafiz Abdul. (1993): ‘A Study of Attitudes of Teachers and Parents of Azamgarh District Towards Muslim Girls’ Education (M.Ed. Dissertation)’, New Delhi: Dept. of Education, Jamia Millia Islamia.

- Madan, T. N. (1976): ‘Muslim Communities of South Asia’, (Revised and enlarged edition, 1995), Vikas Publishing House, New Delhi. - (ed) (1992): Religion in India, Oxford University Press, Delhi.

- Mann, Elizabeth. A. (1992): ‘Boundaries and identities: Muslims, Work and Status in Aligarh’, New Delhi: Saga, See also: Elizabeth A. Mann, (1989): ‘Religious, Money and Status: Competition for Resources at the Shrine of Shah Jamal, Aligarh’, in Muslim Shrines in India, edited by Christian W. Troll, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, pp. 145-171.

- Maqbool, Shahid. (1969): ‘Muslims Representation in U.P. Services Since Independence’, Radiance’, pp. 5-6.