COMPARATIVE PLANNING

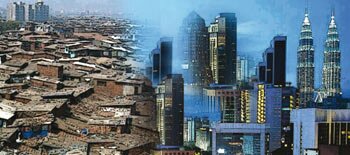

A Tale of Two Countries:India and Malaysia

Amir Ullah Khan Economist,The India Development Foundation and Edith Cowan University 9/19/2010 3:43:50 AM

Tunku Abdur Rehman was born three years after Jawaharlal Nehru, in a rich family, and in 1925 went to Cambridge to study law. Racial discrimination there made him resolve to fight for independence. Tunku headed the Alliance party, won elections in 1955 and in 1957 persuaded the British to give up and make Malaysia a free country. Ten years after Jawaharlal Nehru did the same in India, Tunku became the first Prime Minister of free Malaysia. And remained Prime Minister till 1970 having won three straight elections. While Nehru gave to his country a Tryst with destiny, Tunku declared "Merdeka" (independence).

Both countries initiated a planning process, and Malaysia's Economic Planning Unit became powerful and influential. The New Economic Policy was launched in 1969, with the state announcing large scale reservations for the local Malay Muslim population referred to as the Bhumiputras. The Malays were agriculturists, the Chinese dominated industry and the Indians were employed in the service sector. Reservations for Bhumiputras were given in housing, scholarships and ownership of public listed companies. In India, reservations gave to the poor access to poorly paid jobs and to the illiterate, a right to seats in educational institutions. And now as Malaysia starts dismantling reservations, it can show how its policy actually helped bringing down poverty and increasing representation.

Everywhere you see are captions celebrating Ramzan in Malaysia. The country is fasting, Malaysians use the Sanskrit work upvas, hari raya means the day of celebration referring to Eid ul Fitr and the air is filled with excitement and celebration. There is one hoarding that catches your attention as soon as you land. "There are only 500 tigers left" says the hoarding. In Kuala Lumpur, the conservationists are talking of the falling number of Malayan tigers. With 1411 tigers left, we were ahead of the Malaysians by far. Alas, for the next few days, as I watched TV and read Malaysian papers, I realised there was nothing else we were better at.

Everywhere you see are captions celebrating Ramzan in Malaysia. The country is fasting, Malaysians use the Sanskrit work upvas, hari raya means the day of celebration referring to Eid ul Fitr and the air is filled with excitement and celebration. There is one hoarding that catches your attention as soon as you land. "There are only 500 tigers left" says the hoarding. In Kuala Lumpur, the conservationists are talking of the falling number of Malayan tigers. With 1411 tigers left, we were ahead of the Malaysians by far. Alas, for the next few days, as I watched TV and read Malaysian papers, I realised there was nothing else we were better at.

Malaysia is indeed a fascinating country. Its per capita income at more than 8000 USD a year is ten times that of India's per capita income.

Illiteracy is low (about 95% are literate) and life expectancy high. Nearly half of India's population remain illiterate and the average Indian expects to live for 64 years, a full ten years lesser than the average Malaysian.

Malaysia was a poor country not very long ago. It is a heterogeneous country with Malays, Chinese and Indians scattered all over. The Dutch ruled for around two hundred years and then gave much of Malaysia to the British.

Colonial rule everywhere went along similar lines. Exports were encouraged, Malaysia discovered tin way back in the 17th century, and the European market demanded large amounts of tin. The British, having come in attracted by this metal, also used the climatic zone there to grow rubber and palm.

After the elections in 2008, the new Democratic Party in Penang announced it would do away with all reservations. Last year, the Prime Minister of the country announced several steps towards abolishing the reservation for the sons of the soil in the services sector. The equity quotas and the compulsory local shareholding for foreign companies too is on its way out. The purpose of ensuring ownership of equity for the local Malay achieved, it is time for investment to be freed up so foreign funds could be attracted. In India, this seemed to have escaped the policy maker. The under privileged were given reservations and they occupied lowly jobs, never in ownership of wealth. Even in Malaysia, reservations must have bred inefficiency and nepotism, but in India they did not even seem to have empowered the beneficiary.

Malaysia embarked on reforms early. By the early seventies, most inefficient public sector was privatised. While India was going full steam ahead with a spree of nationalisation, Malaysia was inviting private domestic and foreign investment. Agriculture that was the main occupation in Malaysia, accounted for over 42 percent of the GDP in 1970 and ten years later was down to nine percent. Manufacturing rapidly grew and in 1980, more than 30 percent of the GDP would come from industry and manufacturing. In contrast, Indian manufacturing has contributed less than 25 percent to the economy for more than 40 years now and agriculture continues to employ more than half the working population even today.

As the demand for tin fell, rubber plantations grew. And then the country made a switch to palm oil. Today exports of palm oil contribute substantially to forex earnings. Forests were sources of much of the timber trade that Malaysia depended on in the first half of the twentieth century.

However, responsible forest policy has ensured that even now more than 50 percent of Malaysia is covered with forests. In India, the figure is an exaggerated 18 percent today. Trade with Britain came down but almost immediately the United States became a large partner. Relations with Japan were improved and Malaysian industry benefitted from Japan's technology and investment. While India was backing the USSR, Malaysia first cultivated the US, then Japan and now has flourishing trade ties with China.

The interest rates have always been low, inflation kept in check even when the economy was growing at above seven percent year after year for the two decades of the seventies and the eighties. Trade with neighbours was encouraged and Malaysia keeps an open border with Thailand for trade purposes. India tried this with Nepal and Bhutan but just could not sustain a cordial relationship. And less said about Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, the better. Singapore was proving to be difficult state in the federation, it was allowed to peacefully opt out and become a peaceful and cooperative neighbouring country. India meanwhile kept dallying with a reluctant Kashmir and sixty years later wonders if the costs justify the benefits.

The interest rates have always been low, inflation kept in check even when the economy was growing at above seven percent year after year for the two decades of the seventies and the eighties. Trade with neighbours was encouraged and Malaysia keeps an open border with Thailand for trade purposes. India tried this with Nepal and Bhutan but just could not sustain a cordial relationship. And less said about Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, the better. Singapore was proving to be difficult state in the federation, it was allowed to peacefully opt out and become a peaceful and cooperative neighbouring country. India meanwhile kept dallying with a reluctant Kashmir and sixty years later wonders if the costs justify the benefits.

The Malaysian society is diverse and celebrates this heterogeneity. Muslims girls wear the hijab, the Chinese and the Indians wear modern dresses, and no one could be bothered. Halal restaurants abound. In many ways, a modern progressive country that believes in its democracy, its tradition and its economic strengths. Finally, the most telling example; 12 years ago, the 1998 Commonwealth games were hosted in Kuala Lumpur. With minimum fuss. The facilities were up and ready well on time. Malaysia, with its 25 million population, finished fourth overall behind Australia, England and Canada, winning 10 gold medals with an overall medal tally of 36, while India had seven and 25 respectively. In the next few days, we will know if we can do better.

It was not that the country did not face crises. Be it racial strife, political turmoil, xenophobia, Malaysia seems to have handled it all with equanimity. The mid nineties saw an enormous currency crisis, but handled well enough for the economy to bounce back quickly. The currency was devalued like never before, and exports quickly rose to fund deficits.

Corruption is regular news in the newspapers. Getting licenses to operate business or work in the country is still difficult. However, in disclosure norms and in investor protection Malaysia ranks among the best. This quarter the Malaysian economy grew at more than 10 percent, and much like India, surprised itself with this spectacular increase.

(The views expressed in the write-up are personal and do not re?ect the official policy or position of the organization.)

<

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

*

|

| Name: |

* |

| Place: |

* |

| Email: |

* *

|

| Display Email: |

|

| |

|

| Enter Image Text: |

|

| |

|