GROWTH OR DEVELOPMENT

Growth Experiences During Post-Reform Period in India

Basanta K. Sahu, Faculty -- Economics & Trade Policy, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade New Delhi 5/29/2011 12:33:14 AM

India continues to face the paradox of some backward states in the north and eastern regions of the country with abject poverty while some progressive states in west and southern regions registering dynamic growth. Though overall economic growth has been dynamic for the economy as a whole and in some states, having better infrastructure, sectoral growth and state specific policy and better governance some laggard states remain backward despite of liberal macroeconomic policy environment. While few sectors like in services and non-farm sector and in urban areas exhibited faster growth, poverty is concentrated in agriculture and in rural areas. Till recently, some backward states like Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Odisha became epic center of poverty and volatile growth. On the other hand, states like Gujarat and Tamil Nadu have experienced higher economic growth and rapid reduction of rural poverty than national level. Interestingly, the diverse growth-poverty-disparity scenario has been pronounced at sub-national level during the reform and post reform period. This has been also reflected in terms of uneven human development, pervasive gender inequalities, inter-state poverty disparities and fluctuating growth. Therefore, the issue of growth and poverty nexus has been reemerged as one of the key policy debates and concerns among the policy makers, leaders, development planners and researchers. To achieve twine objectives of growth and equity that translate growth into faster poverty reduction and human development focus has been on inclusive growth.

India continues to face the paradox of some backward states in the north and eastern regions of the country with abject poverty while some progressive states in west and southern regions registering dynamic growth. Though overall economic growth has been dynamic for the economy as a whole and in some states, having better infrastructure, sectoral growth and state specific policy and better governance some laggard states remain backward despite of liberal macroeconomic policy environment. While few sectors like in services and non-farm sector and in urban areas exhibited faster growth, poverty is concentrated in agriculture and in rural areas. Till recently, some backward states like Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Odisha became epic center of poverty and volatile growth. On the other hand, states like Gujarat and Tamil Nadu have experienced higher economic growth and rapid reduction of rural poverty than national level. Interestingly, the diverse growth-poverty-disparity scenario has been pronounced at sub-national level during the reform and post reform period. This has been also reflected in terms of uneven human development, pervasive gender inequalities, inter-state poverty disparities and fluctuating growth. Therefore, the issue of growth and poverty nexus has been reemerged as one of the key policy debates and concerns among the policy makers, leaders, development planners and researchers. To achieve twine objectives of growth and equity that translate growth into faster poverty reduction and human development focus has been on inclusive growth.

Post-reform macro development experiences in India show that higher rate of economic growth has been achieved with disproportionate poverty and inequalities across groups and regions leaving more space for socio-economic exclusions to continue, especially in lagging states and regions. Though importance of inclusive growth on faster poverty reduction has been debated over period varying results at sub-national and sub-regional levels during last few years, the post-reform period growth experience of many backward states found not only low but instable and highly volatile. In this context, the present paper discusses some on key inter-related elements of inclusive growth: performance of agriculture, poverty reduction, human development and regional disparities in some backward states in India in general and examines the performance of Odisha in particular.

Post-reform macro development experiences in India show that higher rate of economic growth has been achieved with disproportionate poverty and inequalities across groups and regions leaving more space for socio-economic exclusions to continue, especially in lagging states and regions. Though importance of inclusive growth on faster poverty reduction has been debated over period varying results at sub-national and sub-regional levels during last few years, the post-reform period growth experience of many backward states found not only low but instable and highly volatile. In this context, the present paper discusses some on key inter-related elements of inclusive growth: performance of agriculture, poverty reduction, human development and regional disparities in some backward states in India in general and examines the performance of Odisha in particular.

Though the backward states such as Odisha, Bihar and UP were the latecomer to experience high growth but their performance continues to be a major concern. Here we have made a modest effort to discuss some trends of growth and poverty in India vis-à-vis five major poor states (Odisha, Bihar, UP, MP and Rajasthan) during post-liberalization period. Since three major backward states are located in Eastern region which accommodate more than two third of total poor in the country the analysis pertains to the eastern India.

There are good numbers of studies are available on inter-state growth variability and performance of progressive and backward groups of states in India but much is not known about it, especially among major backwards states. For better understanding of the growth and poverty nexus in India we have focused on growth and poverty performance of these states during the last two decades. Mathur (2001) found a steep acceleration in the coefficient of variation of per capita incomes in the post-reform period of 1991-96. A tendency towards convergence was noticed within the group of middle income states, while divergence was evident within the groups of high and low income states. Kurian (2000) attempted a comparative analysis of 15 major states in respect of inter-state disparities in demographic characteristics, social characteristics, magnitude and structure of SDP, poverty ratio, developmental and non-developmental revenue expenditures bearing on social and economic development. He found a sharp dichotomy between the forward and backward groups of states1. Bhide and Shand (2000) pointed out the stark differentiation between “progressive” and “backward” states in India. While four fastest growing states (Maharastra, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal) together accounted for 56 percent of the growth in real NSDP in the 1990s and experienced high growth in all three major sectors of agriculture, industry and services, laggard states such as Odisha and Assam fared badly in all the three sectors. Dholakia (1994) found that the patterns of SDP growth in Indian states over the 30-year period 1960-90 were indeed very diverse. Majority of the states experienced shift in the growth rate either in later 1960s or in early 1970s, many years ahead of the shift in the growth rate at the national level in 1981-82. Only five states (Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu and Arunachal Pradesh) experienced the growth rate remained stable while in backward states it decelerated at different time points. For instance it declined in Odisha in 1967-68 despite of high growth rate for the state 1960-61 to 1967-68. Similarly, in Bihar the growth rate accelerated from 1967-68 by 3.6 percentage points and in West Bengal from 1982-83 by 2.6 percentage points. Krishna (2004) argued that the growth rates for the different states calculated by Dholakia (1994) are not consistent because of the price deflators used for obtaining constant price series appear to be different from the ones used by others. The absence of appropriate state-specific price deflators is a serious problem faced by users of SDP data series for Indian states. The data for the different states and all-India may not be entirely comparable and this fact has to be kept in mind in any analysis using these data bases. However, there has been some improvement in SDP data over period. Krishna (2004) found that while in the 1980s all states improved their growth performance relative to the previous two decades, the performance in the 1990s was quite uneven. With acceleration of growth rate at all India level some states like Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, West Bengal and Kerala fared exceedingly well some others managed to improve their performance (Gujarat and Maharastra) during the 1990s. On the other hand some better performed and pro-reformed states (Haryana, Punjab and Andhra Pradesh) suffered in the early 1990s. As regard to backward states there was a deceleration of growth in Bihar, Odisha, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. The interstate variability of growth rates in this period also increased indicating instability of growth (Krishna, 2004). Sachs et al (2002) note that there are major differences across Indian states in the area of policy reform and many socio-economic factors in convergence. While most of the studies have achieved some success in accounting for the differences in growth rate differences across states (and over time in the case of panel regressions), they have not helped in reaching a consensus on convergence or divergence or in identifying the growth determinants

Growth Poverty Nexus in Backward States in India

Economic growth has often been perceived by development economists and policy makers as key to handle persistent poverty  and stagnation at macro level and convergence. In particular, growth theory is not so concerned with poverty and inequality between rich and poor groups within a society. Economic growth is necessary for poverty reduction, but the link between the two is not automatic. In Indian context the economy has registered sustained high growth rate of 7-9 percent during post-liberalization and post-financial crisis period. Unfortunately, the growth has been uneven during last two decades across states and sectors. It has multiplied incomes but also caused increasing insecurity, particularly, among low income groups and in rural areas. Though higher growth is required for stability in the system and to improve people’s lives but benefits of growth has been uneven and it resulted in widening gap between groups and regions. The means to provide social protection for all now exist, what is required is an effective system to reach the benefits.

and stagnation at macro level and convergence. In particular, growth theory is not so concerned with poverty and inequality between rich and poor groups within a society. Economic growth is necessary for poverty reduction, but the link between the two is not automatic. In Indian context the economy has registered sustained high growth rate of 7-9 percent during post-liberalization and post-financial crisis period. Unfortunately, the growth has been uneven during last two decades across states and sectors. It has multiplied incomes but also caused increasing insecurity, particularly, among low income groups and in rural areas. Though higher growth is required for stability in the system and to improve people’s lives but benefits of growth has been uneven and it resulted in widening gap between groups and regions. The means to provide social protection for all now exist, what is required is an effective system to reach the benefits.

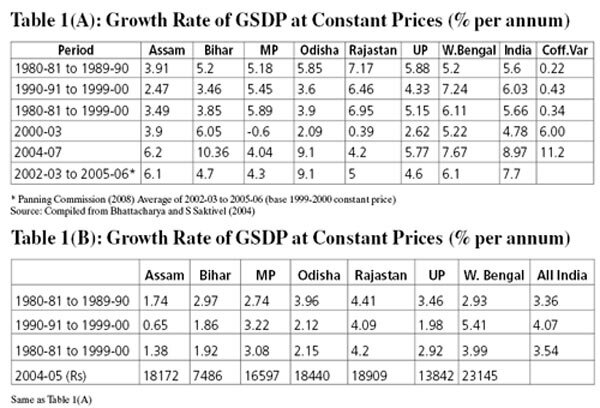

Poverty started a pronounced and steady decline in India as of the 1960s and 1970s (Datt and Ravallion 1998). The contribution of agriculture in terms of improved farm technology and green revolution resulting boost to productivity in agriculture that made poverty reduction in the 1970s but it did not continue in the 1990s and 2000s. Though, the declining poverty trend has been sustained after 1980s, despite of productivity impact of the green revolution had been exhausted in agriculturally developed states, poverty reduction was also found slow or halted in agriculturally backward states, when their growth was lower than national average. It resulted in increasing inter-region and inter-sector inequality across the country. The data presented in the table-1 substantiate it.

Till 1991 when markets and trade were not truly liberalized and higher competition and entry of external investment were not accelerated, growth performance continued depend on agriculture, manufacturing and personnel and administrator's reforms and structural adjustments in the 1990s resulted in experience of a higher growth and improvement in trade sector. But agriculture and small and medium manufacturing sectors were not the key contributors to growth. Service sector led growth perhaps given over importance than primary sector and agriculture in particular. It was also observed that unlike in the 1980s, in the 1990s poverty reduction appears to have slowed down and level of poverty even fluctuated in the 1990s. It indicates that the benefits of the economic reforms accrue differently and there were winners and losers, both within and across regions and sectors.

Growth Pattern in Backward States

It may be seen the data presented in table - 1(A) that the growth pattern among select backward states was quite dissimilar and more so during post-reform period. It was mostly characterized by considerable instability. While many states from both forward and backward groups improved their growth performance considerably in the 1980s some backward states received a setback, particularly, in the second half of the 1990s. Among backward states, while MP and Rajasthan forged ahead with better growth performance, Odisha and Bihar experienced dismal growth after mid 1990s.

On the other hand, volatility of growth appears to be a dominant characteristic of the Indian states apart from instability. Krishna (2004) found three backward states (Odisha, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh) in the four most volatile states over the long period of 1970-71 to 1995-96. While the volatility of growth at the national level was lower in the 1990s than in the 1980s, two backward states (Madhya Pradesh and Odisha) were among the most volatile states. The trend continued during 1990s, as Odisha and Bihar experienced sharp increasing in volatility in contrast to decline in volatility at the national level. Its adverse impact on poverty reduction was also experienced in these states. We have discussed it in detail in subsequent sections.

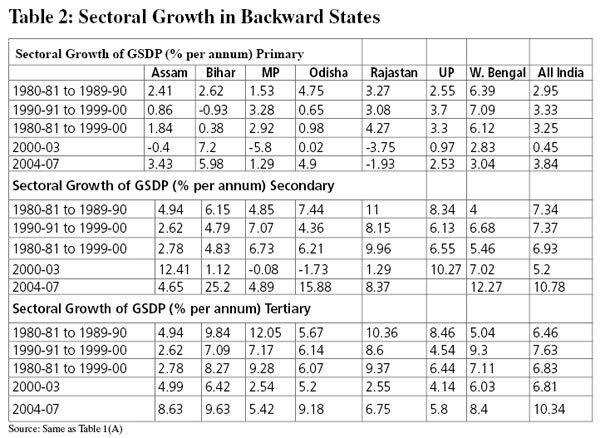

The data presented in the Table - 2 shows that growth rates of backward states increased considerably in the post-reform period as the coefficient of variation of growth rates increased in the 1990s. Growth was accelerated in the states where agriculture has performed better. However, growth of primary sector decelerated in the agriculturally backward states except Bihar during early 2000s. It suggests that agricultural growth has positive impacts on overall growth performance of backward states.

Major Trends of Growth Pattern in Backward States

- The growth rates at national level in the 1980’s and in the post reform period broadly similar at 5.6% - 6% per annum but it varies across states and among backward states.

- Deceleration in growth rate after mid 1990s was found in Odisha, Bihar, Assam and UP while other states experienced acceleration in growth.

- MP and Rajasthan suffered setback in the first half of the current decade whose performance was satisfactory in the 1990s.

- States which have grown faster in the post reform period do not show rapid reduction in poverty.

- Some of the states which did not grow very fast show higher reduction in poverty indicating impact of other factors on incidence of poverty.

- Even in high growth states which have done well in reducing poverty, some regions and groups get left out in the growth process.

- The links between agricultural growth and poverty reduction much more pronounced in backward states in Eastern India.

States taking advantage of the reforms of the 1990s which allowed much latitude in policy making at the state level appears to have performed better than other states. Within the backward group a tendency towards divergence was pronounced during reform period though it was also noticed within the groups of high income states. The reverse trend was observed in the 2000s.

Another important aspect of backward states lies in difference in growth strategies pursued by them. On the one hand, through their sectoral reforms and stringent fiscal measures as the case of Odisha, MP and Rajasthan have exhibited their effort to achieve high growth but did not succeed equally. Investment in agriculture in Bihar and UP has resulted in better growth performance and poverty reduction. Infrastructure promotion policies, investment in irrigation and other social development policies in West Bengal, MP and Rajasthan has resulted in higher growth and faster poverty reduction.

Some high growth states have targeted their basic infrastructure on imitating the most progressive states, whereas some backward states followed over dependence on central assistance and minimizing expenditure on core areas such as farm investment, social sector development while exercising fiscal restrain during reform period as a part of structural adjustment policy. Some of these states lack capacity to absorb central assistance as there were incidence unutilized central fund in the backward states like Odisha (Rao, 2009). There is also lack of understating and capability to tune state level policy with national level policy to achieve the goal of sustained high growth and poverty reduction. This might have worked for the states like Odisha for a longer period and for others states in different sub-periods. This has weaken the regional growth performance driven by the under utilization of local resources and comparative advantages by a static view of poverty reduction.

From the above discussion it is evident that the need for higher and sustained growth is the way out of unacceptable level of poverty, particularly in backward states and in eastern region. The growth process needs to create adequate productive avenues and incomes in both urban and rural areas to accelerate local growth motors. High and sustained growth is necessary but following suitable state level policy is also important to benefit from macroeconomic policy reforms at national level. Failure of some backward states to implement state specific policy and continue it further to use central assistance effectively in the policy regime seems instrumental in divergence at state level and its impacts on poverty. Therefore, it is important to enhance capability of backward states in formulating suitable policies at state level and to benefit from the macroeconomic reforms effectively in order to realize meaningful growth poverty nexus.

Poverty in Backward States In India

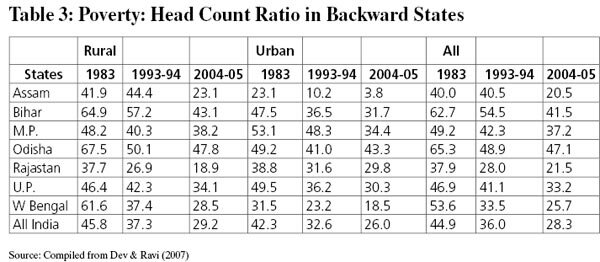

There are debates around the intensity of antipoverty effectiveness of growth in the pre-reform and post-reform period in India and between progressive and backward states. But sharp inter-state differences among the backward states have not been much debated. While economic growth is trickling down very slowly at region and sub-region level, poverty has declined at different pace at different time interval within the poorer states. The level of poverty across the backward states, in terms of the headcount ratio, is presented in Table-3. The poverty line was defined using per capita monthly expenditure, which varied across states both in the level and the reduction of poverty. As progressive reduction in income poverty is crucial in reducing non-income dimensions of poverty, variation in poverty level and reduction indicate the inter-state inequality, which pronounced in backward states.

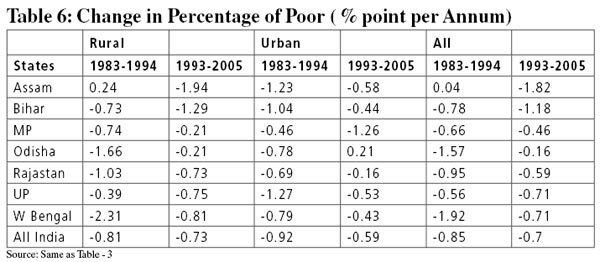

In terms of poverty reduction Assam and Bihar performed better where people below the poverty line decreased by nearly 1.92% point annually in Assam and 1.2% point in Bihar during 1993-2005. Other states suffered slow or stagnant in poverty reduction. Apart from the slow reduction of poverty, government also worried about a lower decrease in poverty ratios in urban areas, compared to rural areas. The trend of slower poverty reduction in urban areas could be due to migration of the poor from rural areas. However, the rate of actual decline of poverty in rural areas could be over estimated. There are also fears that dipping state growth rates and poor performance of agriculture, as witnessed in the case of Odisha, MP and Rajasthan have added to the increase in the BPL population of respective states. Among the poorer states, Odisha has the highest proportion of poor — nearly 50% of its population is below the poverty line.

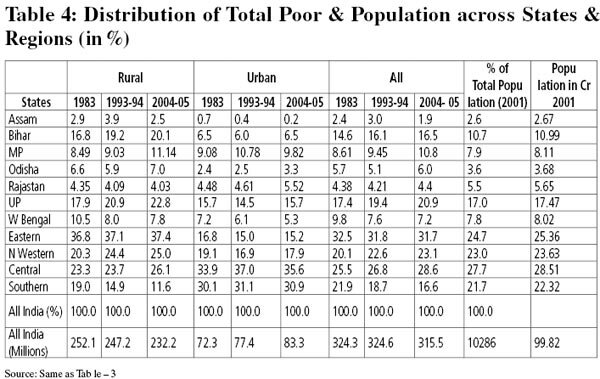

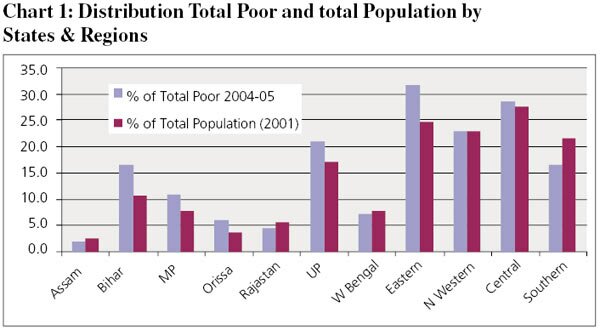

Four backward states Odisha, Bihar, MP and UP turned out as the perennially poor states. Although, the average level of poverty of these states reduced significantly in absolute terms but, as per the recent estimate of poverty for 2004-05, their contribution to total poor in the country has been higher than their share in total population and it was increased substantially over period. This could be attributed partly to a higher rate of population growth as seen in Bihar and UP, and largely to lower rate of poverty reduction vis-à-vis other states.

Another crucial observation that could be made from the movement of poverty ratio is that for the states which had higher poverty ratio to begin with, experienced slower rate of decline in poverty during reform period. This is brought out strongly by the fact that the position of Odisha, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh. Data presented in the Tables 3 and 4 examine the veracity of such claims. The pace of poverty reduction in these states has generally been relatively slow and the level of per capita income has also not been adequate to facilitate faster pace of poverty reduction.

As regard to contribution of backward states in absolute number of poor in India it was increased in all backward states except Assam and Rajasthan during 1993-2005. Assam is the only states whose share in total population is higher than its share in total poor in the country. It shows the disproportion share of poor in backward states and eastern India.

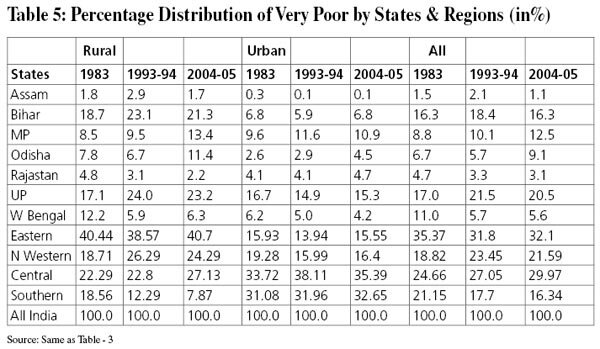

The data presented in the table - 5 indicates that there is no notable improve in reduction of degree of poverty as the proportion of very poor2 increased in MP and Odisha and more or less constatnt in UP, Rajasthan and W. Bengal. It implies that the economic reform does not appear to have triggered any phenomenal changes in the percentage concentration of very poor in UP, MP and Odisha where increase in concentration of the very poor was reported during 1993-2005.

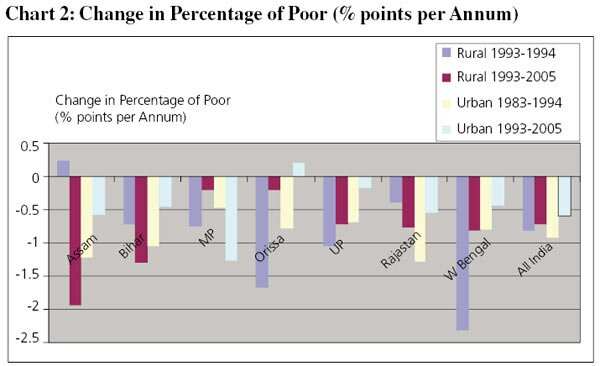

The anti-poverty effectiveness of growth for each of the states analyzed here could be gauged by comparing their average annual rate of decline in poverty ratio. At national the average annual rate of poverty reduction after implementation of economic liberalization was little lower (0.70 percent during 1993-2005) than the rate of poverty reduction earlier (0.85 percent during 1983–93). Among backward states Assam and Bihar reported notable reduction of poverty during 1993-2005 and there was marginal improvement in UP. On the other hand in Odisha the average annual poverty reduction was drastically declined from 1.57% point during 1983-94 to 0.16% point during 1993-2005. There was also marginal decline in pace of poverty reduction in Rajasthan and MP during the early 2000s. These two states had experienced high growth in the mid 1990s with faster poverty reduction.

In urban areas poverty reduction seem halted during post-reform period except in MP as all other backward states reported decline in poverty reduction in urban areas than national average during post-reform period. In Odisha it was increased from - 0.78 percent point per annum during 1983-93 to 0.21 percent point during 1993-2005. The decline was lowest in Rajasthan of 0.16% point. In rural areas both Odisha and MP suffered setback in poverty reduction during 1993-2005 having only 0.21% reduction per annum where as their counterparts Assam and Bihar reported substantial reduction in poverty much higher than national average. However, its overall impacts may be different as UP and Bihar has large number of poor than other states. These differences imply that liberal economic policy measures in the 1990s had different impacts in terms of poverty reduction even within backward states which are often treated as similar kind.

Assam, Bihar and UP had been able to successfully reverse the rising trend in poverty in the pre-reform period as there was notable decrease in poverty in the post-reform period. For the other backward states, there has either been a moderate or negligible increase in anti-poverty effectiveness in post-reform period. All other backward states were registered a decline in effectiveness and in many cases in urban area. There has been a general decline in anti-poverty effectiveness in the post-reform period as compared to the pre-reform period. It is often argued why poverty persists in low growth and backward region despite of substantial central assistance. Part of a possible answer to this relies on the combination of three elements: inequality, agriculture, and human development which perhaps not addressed adequately at state level policy formulation, especially during the reform period.

From the above analysis it is evident that the economic reform process does not seem to have yielded benefit some of the chronically poor states like Odisha, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh both in terms of level of poverty and decline in poverty.

Conclusion

Growth in the backward states during last two decades was characterized by instability and volatility with different degree at different sub-periods. It has corresponding impact on the pace of poverty reduction. Our analysis shows that there was wide variability and volatility of growth and poverty in select backward states in India during last two decades. Though the backward states like Odisha and Bihar were the latecomer to experience high growth but their performance in poverty continue to be major concern for the policy makers. An increase in poverty ratio in Odisha and Bihar during 2004-05 was reported with setback in agriculture and rural employment growth. We argued that impact of high growth at national level not percolated effectively to these states where poverty continues to concentrate even under more liberal national policy environment. The dispersion of growth rates of states increased considerably in the post reform period which influenced the pace of poverty reduction. Here, new growth theories can shed light on this process.

The analysis of growth and poverty in backward states during pre and post-reform period reiterates that there is need to understand the state specific sectoral and regional growth dynamics and formulate policy accordingly than depending on national level policy to achieve and maintain higher growth and faster poverty reduction. This is necessary for convergence but it seems missing in some backward states, particularly, during post reform period. The paper argues that failure to prioritize sectoral and social development policies well before the reform period in the 1990s and sequencing reform policies in subsequent period could be one of the key factors for poor growth performance of theses states. It is reflected in terms of slower pace of poverty reduction, poor performance of agriculture growth, increasing regional disparities and uneven social and human development. However, few backward states like Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan performed better than their counterparts. An increase in poverty ratio in Odisha and Bihar during 2004-05 was reported with setback in agriculture and rural employment growth. Interestingly, growth performance and poverty reduction was better under more conservative policy environment during the 1980s than the 1990s and 2004-05.

The reasons why these growth-enhancing factors are missing in some states and regions and not in others need more policy attention in regional perspective. Macro level policy interventions may not help all states equally because of their diverse growth potential and capacity to compete with others. For instance, among backward states Odisha, Rajasthan, and MP were more volatile states than UP, Bihar in contrast to notable in volatility at the national level. We strongly suggest suitable sectoral and regional growth oriented policy interventions for sustainable inclusive growth. For instance, policy focus on farm investment and rural infrastructure at state level, especially in agriculturally backward states where growth and poverty reduction has been slow or stagnant resulting in poor and human development could be more growth accelerating than macro level development programmes. However, achieving high growth is not adequate to maintain the pace of poverty reduction in the backward states. Growth should create adequate productive employment and ensure equity. Tardy and high volatility in growth performances of backward states show that they fail to appropriate the benefits of new liberal policies due to lack of state specific sectoral and sub-regional policy approach and they continue to bear disproportionate share of poor people with dismal performance of agriculture. The paper strongly argues that calibrated effort is needed to correct some growth retarding factors at state and sub-regional level and prioritize sectoral development policies that augment growth and facilitate equity and faster poverty reduction.

The reasons why these growth-enhancing factors are missing in some states and regions and not in others need more policy attention in regional perspective. Macro level policy interventions may not help all states equally because of their diverse growth potential and capacity to compete with others. For instance, among backward states Odisha, Rajasthan, and MP were more volatile states than UP, Bihar in contrast to notable in volatility at the national level. We strongly suggest suitable sectoral and regional growth oriented policy interventions for sustainable inclusive growth. For instance, policy focus on farm investment and rural infrastructure at state level, especially in agriculturally backward states where growth and poverty reduction has been slow or stagnant resulting in poor and human development could be more growth accelerating than macro level development programmes. However, achieving high growth is not adequate to maintain the pace of poverty reduction in the backward states. Growth should create adequate productive employment and ensure equity. Tardy and high volatility in growth performances of backward states show that they fail to appropriate the benefits of new liberal policies due to lack of state specific sectoral and sub-regional policy approach and they continue to bear disproportionate share of poor people with dismal performance of agriculture. The paper strongly argues that calibrated effort is needed to correct some growth retarding factors at state and sub-regional level and prioritize sectoral development policies that augment growth and facilitate equity and faster poverty reduction.

End-notes

1 Kurian (2000) classified the states into “Forward” states consisting of Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharastra, Punjab and Tamil Nadu, while the “backward” states consist of Assam, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal

2 The Very Poor is defined as people whose per capita expenditure lies below three fourth of the poverty line.

References and Additional Thinking

- Banerjee, Abhijit and Thomas Piketty. “Top Indian Incomes, 1922-1998.” CEPR Discussion Paper, 2004.

- Bhalla G.S, and G. Singh (2009), Economic Liberalization and Indian Agriculture: A State wise Analysis, Economic & Political Weekly, No.52, December 26

- Bhattacharya B B, and S Saktivel (2004), Regional Growth and Disparities in India: A Comparison of Pre and Post Reform Decades, Working Paper, Institute of Economic Growth, Delhi

- Bhide, S. and R. Shand (2000), “Inequalities in Income Growth in India Before and After Reforms”, South Asia Economic Journal, Vol. 1, No.1, March, pp. 19-51.

- Datt, G, and M Ravallion, (1998) “Farm Productivity and Rural Poverty in India”, Food Consumption and Nutrition Division Paper No 42, International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Deaton, A, and J Drèze (2002) “Poverty and Inequality in India: A Reexamination”, Working Paper 107, Princeton University.

- Dev S.M. and C. Ravi (2007), Poverty and Inequality: All India and States, 1983-2005, Economic & Political Weekly, February 10.

- Dholakia, R. H. (1994), “Spatial Dimension of Acceleration of Economic Growth in India , ‘Economic and Political Weekly’, February 25 and 26. August 27,

- Krishna K.L, (2004), Pattern and Determinants of Economic Growth in Indian States, Working Paper No 144, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER)

- Kurian, N. J. (2000), “Widening Regional Disparities in India: Some Indicators,” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol XXXV NO. 7, pp. 538-550. February 12-18.

- Mathur, A. (2001), “National and Regional Growth Performance in the Indian Economy: A Sectoral Analysis”, paper presented at National Seminar on Economic Reforms and Employment in Indian Economy, IAMR.

- Planning Commission (2008), Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007–2012) Volume - III, Agriculture, Rural Development, Industry, Services and Physical Infrastructure, OUP, New Delhi

- Rao. C.H.H. (2003), Reform Agenda for Agriculture, Economic and Political Weekly February 15, 2003

- Rao. M. G, (2009), Regional development for inclusive growth, Business Standard, 6th Oct 2009

- Roy Choudhury, U.D. (1993), “Inter-state Variations in Economic Development and Standard of Living”, NIPFP, New Delhi.

- Sachs, J.D., N. Bajpai and A. Ramiah (2002), “Geography and Regional Growth” The Hindu, February 25 and 26.

(Basanta K. Sahu is a faculty member in Economics & Trade Policy, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, New Delhi. He has about fifteen years of professional experiences in policy research & analysis, teaching and research guidance. Some of his current research works include pro-poor development policy, regional growth & poverty, household risk coping behaviour, drought & food insecurity and microfinance. He has extensively worked on agrarian constraints, non-farm sector, non-farm sector, gender and livelihood issues. Some of his select research projects are funded by ICSSR, IRRI (Manila), The World Bank, ADB, NABARD, Planning Commission of India.

The views expressed in the article are personal and do not reflect the official policy or position of the organisation.)

<

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

*

|

| Name: |

* |

| Place: |

* |

| Email: |

* *

|

| Display Email: |

|

| |

|

| Enter Image Text: |

|

| |

|