GROWTH OR DEVELOPMENT

Sustainable Development of Agriculture

U.Sankar, Madras School of Economics 5/30/2011 3:18:02 AM

The Brundtland Commission (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987), defined sustainable development as "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." Arrow, Dasgupta, Goulder, Mumford and Oleson (2010) take the view that economic development should be evaluated in terms of its contribution to intergenerational well-being. They show that intergenerational well-being would not decline over a specified time-period if and only if a comprehensive measure of the economy's wealth were not to decline over the same period. By wealth they mean the social worth of an economy's entire productive base i.e., not only reproducible capital goods or human capital but also population, public knowledge, and the myriad of formal and informal institutions that influence the allocation of resources.

The Brundtland Commission (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987), defined sustainable development as "development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." Arrow, Dasgupta, Goulder, Mumford and Oleson (2010) take the view that economic development should be evaluated in terms of its contribution to intergenerational well-being. They show that intergenerational well-being would not decline over a specified time-period if and only if a comprehensive measure of the economy's wealth were not to decline over the same period. By wealth they mean the social worth of an economy's entire productive base i.e., not only reproducible capital goods or human capital but also population, public knowledge, and the myriad of formal and informal institutions that influence the allocation of resources.

The UN bodies and many governments consider three dimensions of sustainable development — economic, social and environmental. Economic efficiency is necessary for achieving the maximum possible growth with limited resources. The social dimension is in terms of equity, particularly intra generational equity. Poverty eradication is one of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs); it has become a global public good by global public choice. The environmental dimension captures internalization of environmental costs of pollution and natural resource degradation in decision making of all economic agents and intra generational equity. It is being realized that natural resource degradation and pollution are not just environmental challenges; they threaten poverty eradication and achievement of the MDGs.

Until recently, the major goal of India’s development had been economic growth. The Eleventh Plan (2007-12) articulated the need for pursuing an inclusive growth strategy. This broad vision includes ‘several inter-related components: rapid growth that reduces poverty and creates employment opportunities, access to essential services in health and education especially for the poor, equality of opportunity, empowerment through education and skill development, employment opportunities underpinned by the National Rural Employment Guarantee, environmental sustainability, recognition of women’s agency and good governance’.

Until recently, the major goal of India’s development had been economic growth. The Eleventh Plan (2007-12) articulated the need for pursuing an inclusive growth strategy. This broad vision includes ‘several inter-related components: rapid growth that reduces poverty and creates employment opportunities, access to essential services in health and education especially for the poor, equality of opportunity, empowerment through education and skill development, employment opportunities underpinned by the National Rural Employment Guarantee, environmental sustainability, recognition of women’s agency and good governance’.

Even though the linkages between growth and environment and between poverty and environment are known that they have not been incorporated adequately in Indian planning and public policies. Economic growth is subject to ecosystem constraints. Dasgupta (1993) explores the two-way links between poverty and environmental resource base. The Millennium Ecosystems Assessment (2005) depicts the strength of linkages between categories of ecosystem services and components of human well-being that are commonly encountered and includes indications of the extent to which it is possible for socioeconomic factors to mediate the linkage. It also notes that other factors — including other environmental factors as well as economic, social, technological, and cultural factors — influence human well-being, and ecosystems are in turn affected by changes in human well-being.

Agricultural Growth, Employment and Rural Poverty

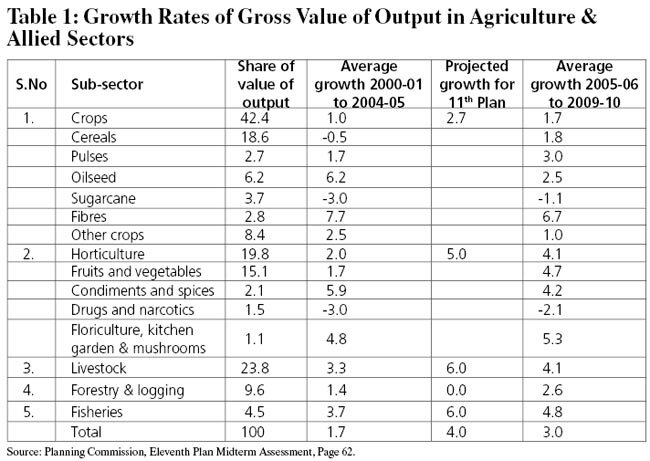

During the first decade of the Millennium the rate of growth of agricultural output was lower than the planned output. The Planning Commission fixed a target growth rate of four percent per annum for the 11th plan .The target of four percent growth in GDP from agriculture and allied sectors was felt necessary to achieve overall GDP growth target of nine percent per annum without undue inflation and generate exportable surplus. Also global experience reveals that growth originating in agricultural sector is at least twice effective in reducing poverty as GDP growth originating in other sectors. There are forward and backward linkages with the non-agricultural sector.

The annual rate of growth of crop output during 2000-01 to 2004-05 was only one percent and during 2004-05 to 2009-10 it was 1.7 percent. These growth rates were close to the overall population growth rate during the decade. The growth rates of higher value added sectors (per hectare of land) namely horticultural, livestock and fisheries outputs were higher. This diversification is desirable as the shares of horticultural and livestock products increase in food budgets as households incomes increase. The forestry output growth rate was lower because of policies related to conservation and sustainable use for forest resources.

The annual rate of growth of crop output during 2000-01 to 2004-05 was only one percent and during 2004-05 to 2009-10 it was 1.7 percent. These growth rates were close to the overall population growth rate during the decade. The growth rates of higher value added sectors (per hectare of land) namely horticultural, livestock and fisheries outputs were higher. This diversification is desirable as the shares of horticultural and livestock products increase in food budgets as households incomes increase. The forestry output growth rate was lower because of policies related to conservation and sustainable use for forest resources.

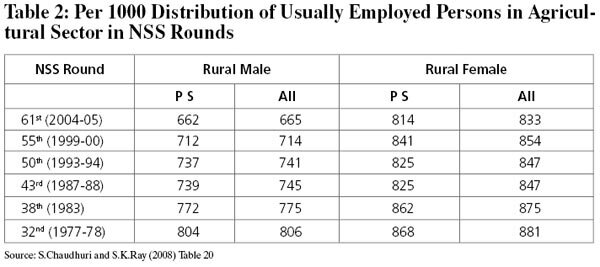

The share of agriculture and allied activities in gross domestic product at factor cost fell from 55.1 percent in 1950-51 to 14.6 percent in 2009-10. This declining share of agricultural sector is consistent with the development experiences of developed countries. What is disconcerting is the very slow shift of employment from agricultural sector to non-agricultural sector. Assuming the share of rural population in total population at 70 percent (72.2 percent in 2001 census) and using an estimate of agricultural employment of 749 persons per 1000 persons employed from 61st Round of National Sample Survey, the share of agricultural employment in total employment is estimated at 52.43 percent. This means that the average value added per employee in the non-agricultural sector is about 6.4 times higher than the value added per employee in the agricultural sector. This order of magnitude widens income inequality between agricultural and non-agricultural sectors and suggests the need for policy changes to achieve the goal of inclusive growth.

In rural areas there has been a slow shift in employment from agriculture and allied activities to other activities. It may be seen from Table 2 that in 2004-05 about two-thirds of rural males and six out of every rural women depended on agriculture. While the percentage of male workers depending on agriculture fell from 80 in 1977-78 to 66 in 2004-05, the percentage of women depending on agriculture showed a small decrease from 88 to 83.

According to Tendulkar Committee report (Government of India (Planning Commission (2009)) rural poverty fell from 50.1 percent in 1993-94 to 41.8 percent in 2004-05; the corresponding change in urban poverty is from 31.8 percent to 25.7 percent. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Programme , which began in the first year of the 11th Plan is expected to reduce the percentage of people below the poverty line in rural areas.

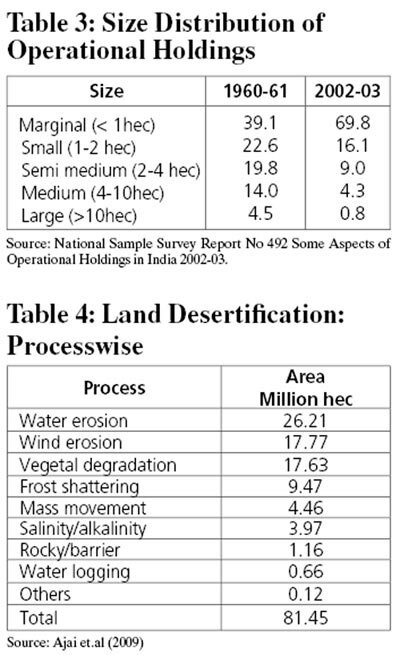

Agricultural Resource Base Land

The rapid increase in population and slow shift of labour from agriculture to non-agriculture is evident in the dominance of marginal farms. In 2002-03 nearly 70 percent of the operational holdings were marginal holdings with size less than one hectare; another 16 percent were small holdings with size between 1-2 hec. See Table 3. The small sizes prevent farmers from adopting improved agricultural technologies and create barriers for accessing credit and adopting improved agricultural practices.

India is facing serious environmental stress in her natural resource stocks. Land desertification and land degradation affect the quality of land, the major capital input in farming.

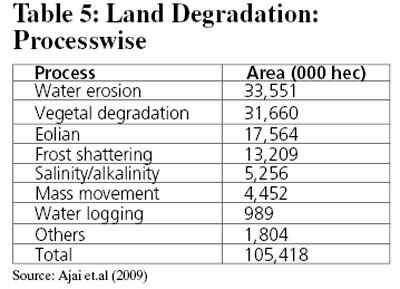

Based on land status mapping carried out for the entire country on 1: 500,000 scale, using multi-temporal Resourcesat AWiFS data, Ajai, Arya, Dhinwa, Pathan and Raj (2009) provide information on land desertification and land degradation in India. Of the geographical area of 328.73 million hec, 81.45 million hec (24.8 percent) land is degraded. The process wise details are given in Table 4. Another 105 million hec of land (32.1 percent of geographical area) is degraded. Thus 57 percent of the geographical area is either desertified or degraded.

Water Resources

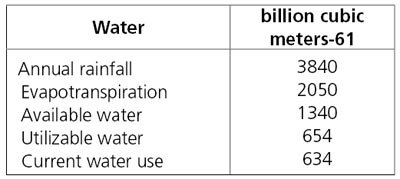

The Eleventh Plan recognized the challenges of water resources management faced by India and the likelihood that these would only intensify over time due to rising population, expected growth in agricultural and industrial demand, the danger of pollution of water bodies and, over the longer term, the effect of climate stress on water availability in many parts of the country.

Referring to a study by Narasimhan and Gaur, the 11th Plan Midterm Assessment gives the following water budget for India:

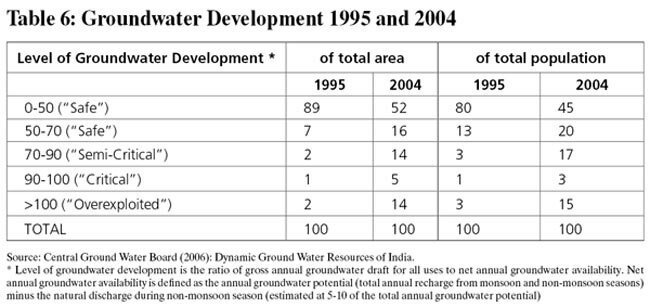

During 1995-96 to 2006-07, on an average, the contributions of surface and groundwater to net irrigated area were 32 percent and 60 percent respectively. There has been a fall in ground water table due to rapid expansion of tube wells .Table 6 gives information about the degree of exploitation of ground water. There is deterioration in water quality. Biological contamination of surface water sources due to poor sanitation and waste disposal resulted in incidence of water-borne diseases throughout the country. Chemical pollution of groundwater, with arsenic, fluoride, iron, nitrate and salinity as the major contaminants is directly connected with falling water tables and extraction of water from deeper levels.

There has been a severe erosion of the financial status of the irrigation systems. At present irrigation revenues cover barely 15 percent of working expenses and only five percent of total costs and losses. As for agricultural pumpsets, zero marginal pricing of electricity and use of energy inefficient pumpsets in most states discourage energy conservation and overuse of water resulting in depletion of water and deterioration of the water quality. Vaidyanathan (2006) argues that access to irrigation leads to a huge increase in the productivity of his land and water should be treated like any other input and priced on the basis of the cost of supply, leaving it to the farmer to decide which combination of inputs (including quantum of irrigation) would be to his best advantage. The rate increases will also incentivize a more careful use of water and lead to choice of socially preferred cropping pattern. These perverse subsides neither meet equity nor environmental sustainability criteria.

There has been a severe erosion of the financial status of the irrigation systems. At present irrigation revenues cover barely 15 percent of working expenses and only five percent of total costs and losses. As for agricultural pumpsets, zero marginal pricing of electricity and use of energy inefficient pumpsets in most states discourage energy conservation and overuse of water resulting in depletion of water and deterioration of the water quality. Vaidyanathan (2006) argues that access to irrigation leads to a huge increase in the productivity of his land and water should be treated like any other input and priced on the basis of the cost of supply, leaving it to the farmer to decide which combination of inputs (including quantum of irrigation) would be to his best advantage. The rate increases will also incentivize a more careful use of water and lead to choice of socially preferred cropping pattern. These perverse subsides neither meet equity nor environmental sustainability criteria.

Fertilisers

At present the nitrogen, phosphatic, pottasic mix is 0.637:257:106. The Midterm Assessment of the 11th Plan notes that the association between fertiliser consumption and food grains production has weakened during the recent years due to imbalanced use of nutrients and deficiency of micro-nutrients, which demands a careful examination and policy action. This imbalance in use of plant nutrients and neglect of micro nutrient deficiencies in Indian soils has led to declining fertiliser response and deterioration of soil health. Implementation of the new policy of nutrient based subsidy is likely to provide incentive for balanced use of fertilisers. Imports of fertilisers now account for more than 40 percent of the domestic consumption. Fertiliser subsidy as a ratio to the value of crop output, which hovered between 3 and 3.5 percent during 2000-06 has risen to more than 10 percent in 2008-09 due to a spike in the price of imported fertilizers.

Soil

Soil

A healthy soil is necessary to ensure proper retention and release of water and nutrients, promote root growth maintain soil biotic habitat and resist degradation. Decline in soil health causes low fertilizer and other nutrients responses resulting in low productivity. There is need for soil testing at farm level for determining an optimum mix of fertilizers and following sound crop management practices.

Policies for Sustainable Agricultural Development

Capital Formation in Agricultural Sector

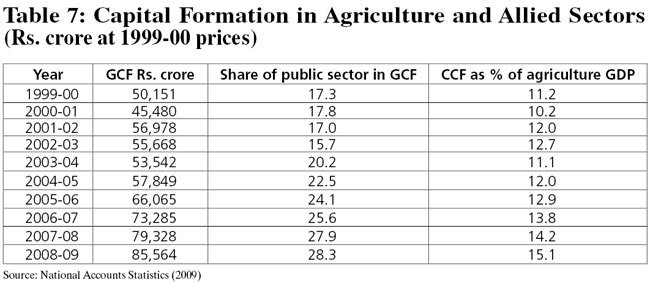

After stagnation, gross capital formation as percent of agricultural GDP has been rising from 2004-05. The share of public investment in the gross capital formation has also picked up from 2003-04. See Table 7.

We need an expenditure switch from subsidies to investments which augment the quantities and qualities of natural resource stocks. The necessary additional resources for capital formation can be generated via (i) phasing out environmentally perverse subsidies such as high subsidies for urea, under pricing of irrigation water and very low/zero pricing of electricity for farm pumpsets; (ii) reducing leakages, and targeting subsidies in the public distribution system to people below poverty line; (iii) rationalization of irrigation charges and agricultural electricity tariffs; and (iv) introduction of user charges/payment for ecosystem services. The policy reforms involve a package of technological, institutional and incentive based reforms.

Technology

India has developed the institutional capacity for using remote sensing data for natural resources management. The National Natural Resources Management System (NNRMS) facilitates optimum utilization of the country’s natural resources through a proper and systematic inventory of the resource availability. The NNRMS covers agriculture, bio resources, water resources, meteorology, cartography and mapping, rural development and other areas. Some important applications of remote sensing technologies in the agricultural sector are preparation of hydro-morphological maps showing areas suitable for targeting points for locating drinking wells ; mapping of wastelands into different categories; integrated surveys for combating drought; biodiversity characterization; disaster management support system; assessment of snow-melt run-off; forest cover mapping; potential fishing zone forecasts; coastal zone mapping and crop area and production forecasts. The full potential benefits of the technology are yet to be realised.

The green revolution helped India in achieving self-sufficiency in food. Now there is a realization that this water intensive and fertilizer intensive technology, along with myopic and perverse pricing policies for fertilizers and irrigation water, are environmentally unsustainable.

We need an ecologically sustainable green revolution. We need more research on appropriate technologies for coarse cereals, pulses and horticultural crops, especially in arid and semi-arid areas. The National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture stresses the need for devising strategies to make Indian agriculture more resilient to climate change. The Mission has to identify and develop new varieties of crops and especially thermal resistant crops and alternative cropping patterns capable of withstanding extremes of weather, long dry spells, flooding and variable moisture availability.

India is emerging a leader in applications of biotechnology to agriculture, medicine and environment. Application of this technology to agriculture may result in improving yield, nutritional improvement, increasing shelf life of fruits and vegetables by delayed ripening ,conferring resistance to insects, pests and viruses, tolerance to abiotic stresses (drought, salt, water-logging) and herbicide tolerance. There are also concerns about transplanting genetically modified seeds developed abroad in Indian soil.

We need technological inputs and institutional support for improving soil health. The site specific Integrated Nutrition Management Programme envisages conjunctive use of chemical fertilizers, organic manures and biofertilisers to enhance nutrient use efficiency, soil health, crop yields and productivity. Gujarat government’s proposal of Soil Health Card Programme is an innovative programme. Under this programme, every farmer takes specimen of the soil from his land to soil testing lab in his district where the scientist examines it for mineral composition. Based on various components of the soil, the farmer is advised to cultivate crops which would get good yield on his land. All this information would be recorded on the soil health cards which would be issued to him. The government also plans to integrate the soil health programme with the e-governance programme which could provide information on nature of soil to farmer from a computer at the village panchayat.

We need public investment in rural infrastructures particularly on road and communication networks for access to markets and information. Public and private investment in post-harvest technologies will not only reduce wastage but also increase value addition and provide greater market opportunities. Kiosks and agricultural digital networks can help in reducing information asymmetries, reducing the intermediation costs and accessing agricultural services timely at lower costs.

Institutional Changes

Reclamation of salt affected lands , bioremediation of contaminated sites and conversion of waste lands to productive uses via agro forestry/corporate management/community based self-governing organizations can increase the cultivated area and create livelihood opportunities for the poor. Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee scheme offers scope for cleaning of rivers, lakes , ponds and wetlands. Implementation of Forest Rights Act, Joint Forest Management schemes and access and benefit sharing provisions of the Biological Diversity Act would incentivize the stakeholders to adopt sustainable management practices.

Policy Changes

We need policies for crop diversification, generation of non-farm opportunities in rural areas and development of agro based industries. Other policy changes needed are (i) implementation of nutrition based subsidy scheme with fertilizer prices linked to minimum support prices (ii) creation of Water Regulatory Authority for allocation and rational pricing of irrigation water as recommended by the Thirteenth Finance Commission (iii) metering of electricity for pumpsets and phasing out electricity subsidies (iv) development of payment for ecosystem services e.g., between forest dwellers and farmers and local bodies in near-by regions for increases in the quantity and quality of water supplied (v) targeting agricultural subsidies and concessional agricultural credit only to small and marginal farmers using unique identification cards.

India, along with other developing countries, must argue in the WTO for immediate removal of distortions in agricultural markets of many OECD countries. The high levels of export subsidies and subsidies coming under amber and blue boxes depress the world agricultural prices and affect the agricultural exports of developing countries. India must enhance technical and institutional support to exporters of agricultural products for complying with the Technical Barriers to Trade and Sanitary and Phyto-sanitary regulations of the WTO .

India, along with other developing countries, must argue in the WTO for immediate removal of distortions in agricultural markets of many OECD countries. The high levels of export subsidies and subsidies coming under amber and blue boxes depress the world agricultural prices and affect the agricultural exports of developing countries. India must enhance technical and institutional support to exporters of agricultural products for complying with the Technical Barriers to Trade and Sanitary and Phyto-sanitary regulations of the WTO .

India’s growth potential and export potential in horticultural products are very high. At present only about 0.5 percent of the value of horticultural products is exported. Accelerating India’s agricultural growth exploiting opportunities provided by globalization is feasible. Kalirajan, Mythili and Sankar (2001).

India along with other mega biodiversity countries is taking efforts for incorporation of country of origin, prior informed consent and access benefit sharing provisions of the Convention on Biodiversity in patent registrations abroad. This would incentivize the guardians of traditional knowledge and biological resources for adoption of sustainable management practices.

Concluding Remarks

India’s agricultural subsidies are below the de minis levels set by the WTO. What we need is expenditure switching from current expenditures, particularly reduction of perverse agricultural subsidies which do not promote equity and environmental sustainability, to capital expenditures which augment the quantity and quality of natural capital stocks. We also need policies which signal farmers about the social costs of different natural resources and ecosystem services and incentivize them to adopt productivity enhancing farming methods and practices, crop diversification and post-harvest technologies for reducing wastes and better price realization. Subsidies must be targeted to achieve equity and environmental sustainability.

Sustainable management of agriculture, forests, fisheries and ecosystem services is necessary for achieving the goals of intra generational equity and inter generational equity. As the dependence of the poor on the natural resource base is relatively higher than for the non-poor, sustainable management of natural resources helps in poverty eradication. The poor also benefits more from greater access to clean water, non-timber forest products and other eco-system services.

References andAdditional Thinking

- Ajai, A. S. Arya, P. S. Dhinwa, S. K. Pathan and K.G.Raj (2009), Desertification/Land Degradation Status Mapping of India, Current Science, Vol. 97, No. 10.

- Arrow, K.J., P.Dasgupta, L H. Goulder, K.J. Mumford and K. Oleson (2010), Sustainability and the Measurement of Wealth, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 16599

- http://www.nber.org/papers/w16599.

- Chaudhuri, S. and S.K.Ray (2008), An Integrated Summary of NSS 61st Round (July2004-2005) on “Employment and Unemployment Situation in India”, Sarvekshana, 94th Issue, Vol. XXVIII No 3 & 4 December.

- Dasgupta, P. (1993), Poverty and Environmental Resource Base, in An Enquiry into Well-Being and Destitution, Oxford University Press UK. Reprinted in U.Sankar (ed) Environmental Economics, Readers in Economics, Oxford University Press, 2001. Paperback: eighth impression 2008.

- Government of India (2009), Report of the Thirteenth Finance Commission, New Delhi

- Government of India (Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation) (2009), National Accounts Statistics 2009, New Delhi.

- Government of India (Ministry of Water Resources Central Ground Water Board) (2006), Dynamic Ground Water Resources of India, New Delhi.

- Government of India (Planning Commission) (2007), Eleventh Five Year Plan, New Delhi.

- Eleventh Plan Midterm Assessment, New Delhi.

- Kalirajan, K.P., G.Mythili and U.Sankar (2001), Accelerating Growth through Globalization of Indian Agriculture, Macmillan India,

- New Delhi.

- Millennium Economic Assessment (2005), Ecosystems and Human Well-Being Synthesis, Island press, Washington DC.

- Sankar, U (2007), The Economics of India’s Space Programme, Oxford University Press, New Delhi.

- Vaidyanathan, A. (2006): India’s Water Resources: Contemporary Issues on Irrigation, Oxford University Press, and New Delhi.

(U.Sankar received Ph.D in economics from University of Wisconsin, Madison in 1967. His research interests have been in applied econometrics, pricing of public utilities, cost benefit analysis of India's space programme and environmental economics. He was Coordinator of the World Bank-Ministry of Environment and Forests Capacity Building Programme in Environmental Economics in India during 1997-2002.He was President Indian Econometric Society in 1994 and Indian Council of Social Science Research National Fellow in 2003 and 2004.He was awarded the University Grants Commission's National Swami Pranavananda Saraswati Award in Economics for 2006. He is Honorary Professor and Coordinator of Trade and Environment Programme of the Ministry of Environment and Forests at Madras School of Economics. He is Member Planning Commission Expert Group on Low Carbon Inclusive Growth Strategy, Member of the Steering Committee on Environment, Ecology and Wild Life for the12th Plan and Fiscal Coordinator of Central Pollution Control Board’s clean Technology Project for SMEs.

The views expressed in the article are personal and do not reflect the official policy or position of the organisation.)

<

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

*

|

| Name: |

* |

| Place: |

* |

| Email: |

* *

|

| Display Email: |

|

| |

|

| Enter Image Text: |

|

| |

|